OpenAI & Georgia Tech: Unpacking LLM Hallucination Mechanics

This is a heavyweight research that holds the promise of completely solving the “mystery of hallucinations.” It’s from the paper “Why Language Models Hallucinate” jointly published by OpenAI and Georgia Tech.

This is a heavyweight research that holds the promise of completely solving the “mystery of hallucinations.” It’s from the paper “Why Language Models Hallucinate” jointly published by OpenAI and Georgia Tech.

The value of this paper lies in that it doesn’t attribute hallucinations to superficial reasons like “model not big enough” or “training data insufficient.” Instead, through rigorous statistical theory and empirical cases, it proves that hallucinations are essentially the product of two core issues: statistical error propagation during the pre-training stage, and evaluation mechanism misalignment during the post-training stage.

In other words, hallucinations are not technical “accidents” but “inevitable results” under existing training and evaluation logic.

This article will tackle with these two core issues to gradually understand the ins and outs of hallucinations and how to solve them.

Introduction to Pre-training Objectives

First, we need to clarify a premise: The pre-training objective of large language models is to learn the probability distribution of human language. Simply put, it’s to let the model know “which sentences are more common and reasonable.” For example, “I eat bread” is more reasonable than “Bread eats me,” and “Sky is blue color” is more reasonable than “Sky is green color.”

Many people think that as long as you feed the model enough “error-free data,” it can only output correct content. But this paper uses mathematics to prove that even if the training data is 100% error-free, the model after pre-training will still produce errors because generating correct content is more difficult than judging whether content is correct.

Understanding the IIV Classification Problem

Here we need to introduce the paper’s core theoretical tool: the IIV (Is-It-Valid) binary classification problem. What is IIV? Its full name is “Is-It-Valid,” which is validity judgment. Simply put, it’s giving the model a sentence and letting it judge whether this sentence is “valid” or “invalid.” Valid means correct, marked as +, and invalid means error, marked as -. This is a typical supervised classification task. The training data contains both correct sentences and randomly generated error sentences, each accounting for 50%.

The paper proves through mathematical derivation a key conclusion: that the model’s generation error rate, that is, the probability of outputting incorrect content, is at least twice its error rate in the IIV classification task. Why is this? Because the generation task essentially contains countless “hidden IIV judgments.”

For example, when the model needs to output “Adam’s birthday is such and such,” it first has to judge in its mind: is this date Adam’s birthday? Is the date format correct? Have I seen this information before? And so on, a series of classification problems. If any classification judgment is wrong, the final generation result will be wrong.

Examples Illustrating Generation Errors

Let’s take an example from the paper for a more intuitive understanding:

The first situation is “spelling judgment,” like “Greetings” and “Greatings.” The model has a high IIV classification accuracy for this type of problem because spelling rules are obvious, so it rarely makes spelling errors when generating. This is why today’s large models basically don’t write typos.

The second situation is “letter counting,” for example, “How many D’s are in DEEPSEEK?” The correct answer is 1. But the DeepSeek-V3 model answered either 2 or 3 in 10 tests, and other models even answered 6 or 7. Why? Because the “letter counting” task has higher IIV classification difficulty. The model needs to first split “DEEPSEEK” into individual letters and then count them one by one. The architecture of many models is not good at handling this kind of fine-grained task, leading to high IIV classification error rate and ultimately incorrect answers.

Interestingly, the paper also mentions that DeepSeek R1 can answer correctly because it uses chain-of-thought reasoning, indicating that the stronger the model’s “fitting capability” for the task, the lower the generation error rate.

Arbitrary Facts and Singleton Rate

The third situation is “birthday fact judgment.” This type of problem has the highest IIV classification difficulty because a birthday is an “arbitrary fact with no patterns,” neither having fixed rules like spelling nor clear steps like letter counting. It all relies on memory in the training data. If Adam’s birthday appears only once in the training data, or even not at all, the model cannot accurately judge “whether a certain date is correct,” the IIV classification error rate will soar, and it will naturally “make up a seemingly reasonable date” when generating.

The paper calls information like “birthdays, paper titles” that has no patterns and relies entirely on memory as “arbitrary facts.” The biggest characteristic of these facts is that there are no learnable patterns, and they completely depend on the frequency in the training data.

For example, “Einstein’s birthday is 03-14” appears thousands of times in the training data, the model’s IIV classification accuracy is close to 100%, and it won’t make mistakes when generating. But for the birthday of a niche scholar that may have appeared only once in an obituary, the model’s IIV classification accuracy will be low, and when generating, it will most likely make up a date.

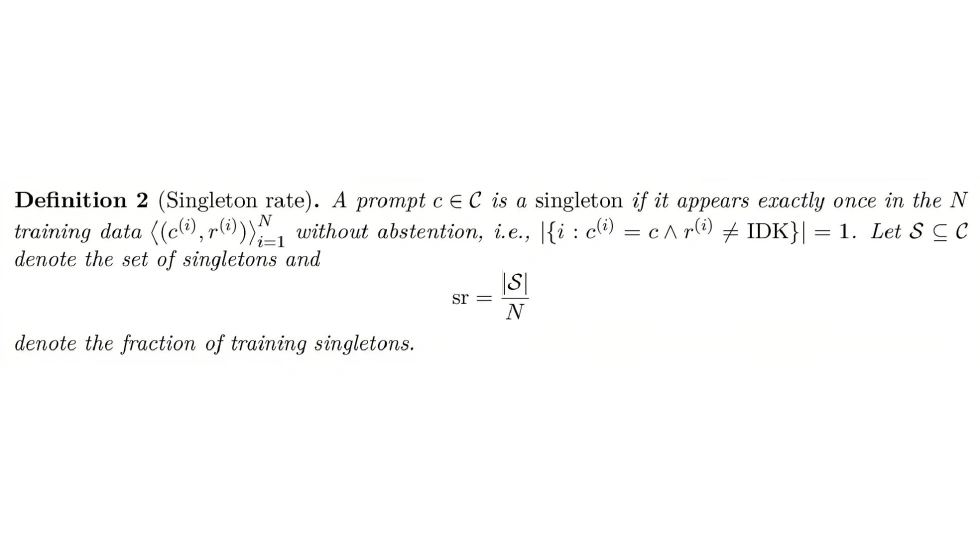

The paper quantifies this error with “singleton rate (sr).” A “singleton” refers to a prompt-response pair in the training data that “appeared only once and is not ‘I don’t know’ (IDK).” The paper proves that for arbitrary facts, the model’s hallucination rate lower bound equals the singleton rate. Simply put, if 20% of birthday facts in the training data are “singleton,” then when the model answers these birthday questions, it has at least a 20% probability of producing hallucinations.

The logic behind this conclusion comes from the “Good-Turing missing mass estimation” proposed by Alan Turing. Simply put, “events that appeared only once in the training data” can be used to estimate the probability of “events that never appeared.”

For example, if you catch 100 fish in a pond, and 20 of the fish species have only been seen once, then the probability of you encountering a new species the next time you fish is probably 20%. Therefore, for the model, the more “singletons,” the more “correct facts” it hasn’t seen, and the more likely it is to use made-up incorrect facts to fill the blanks when generating.

Model Defects and Long-context Understanding

In addition to “arbitrary facts,” the model’s own defects can also cause pre-training errors. For example, the model architecture cannot fit the target concept, or although the architecture is strong enough, it is not well trained. In the paper, this is called the “Poor Models” problem. The most classic example is the defect of “trigram models.”

Trigram models were the mainstream language models in the 1980s-1990s. They could only predict the next word based on “the first two words.”

For example, facing two prompts (“She lost it and was completely out of .” and “He lost it and was completely out of .”), the correct completions are “her mind” and “his mind” respectively. But the trigram model cannot distinguish the possessive pronouns corresponding to “she” and “he” because it only looks at “completely” before “out of,” so it will generate “her mind” or “his mind” as the completion for both prompts, leading to errors.

The paper proves mathematically that for tasks requiring “long-context understanding,” if the model’s architecture has insufficient “fitting capability” (for example, a trigram model’s context window is only 2 words), its IIV classification error will be high, leading to a generation error rate of at least 50%.

For example, the “letter counting” problem mentioned earlier, the reason why DeepSeek-V3 miscounted the number of D’s in DEEPSEEK is essentially due to model defects. Its tokenizer splits “DEEPSEEK” into tokens like “D/EEP/SEE/K” instead of individual letters, making it impossible for the model to directly “count letters.” And DeepSeek-R1, through “chain-of-thought reasoning,” splits the word into individual letters and counts them one by one, essentially using “reasoning ability” to compensate for the model architecture defects, reducing IIV classification errors, and ultimately generating the correct answer.

Additional Factors Affecting Pre-training Errors

In addition to the two core reasons mentioned above, the paper also mentions three important factors that cause pre-training errors:

First is computational complexity. Some problems are “computationally unsolvable.” For example, “decrypting a random encrypted text,” even if the model knows the encryption algorithm, it cannot crack it within limited time. Then it can only output a wrong decryption result because it cannot judge “which decryption result is correct.”

Second is distribution shift. Simply put, the prompts during testing look different from the prompts in the training data.

For example, in the training data, there are few “trick questions” like “which is heavier, a pound of feathers or a pound of lead,” and the model may mistakenly answer “lead is heavier” because “feathers look light.”

For another example, the “letter counting” task, if the training data contains only short words (like “CAT,” “DOG”), and suddenly it’s asked to count a long word like “DEEPSEEK,” the model is prone to errors. This is not because the model didn’t learn well, but because the training data’s distribution didn’t cover this type of situation, leading to increased IIV classification errors.

Third is “Garbage in, Garbage out” (GIGO). Although the paper assumes no errors in the training data, in reality, the training data will inevitably contain errors, rumors, and even some conspiracy theories. The model will learn this wrong information and reproduce it when generating because it cannot judge that this content is wrong.

The paper also points out that GIGO will further increase pre-training errors because the model not only faces “statistical errors” but also the problem of “data pollution.”

Post-training Techniques and Hallucinations

By this point, some friends may ask: “It’s normal to have pre-training errors, but post-training, such as optimization methods like RLHF and DPO, are specifically designed to correct model errors. Why do hallucinations still not disappear after post-training, and even become more severe in some tasks?”

The paper’s answer is quite sharp: It’s not that post-training technologies are ineffective, but that existing evaluation mechanisms are “encouraging hallucinations.”

It’s like when a teacher grades papers, they think making up an answer scores higher than leaving it blank. Students will naturally choose to make up an answer. The same goes for large language model evaluation benchmarks: “making up a seemingly reasonable wrong answer” scores higher than “saying I don’t know.” So the model naturally chooses to hallucinate.

Issues with Evaluation Mechanisms

Now mainstream model evaluation benchmarks almost all use “binary grading” methods, which means 1 point for correct and 0 point for incorrect or abstention. The paper did a survey: among the 10 most influential evaluation benchmarks, 9 are purely binary, and only WildBench gives a weak score for “abstention,” but it’s still lower than “a reasonable wrong answer.”

For example, GPQA is a multiple-choice question with no “I don’t know” option, and the model must choose one. MMLU-Pro is also multiple-choice, with 0 point for abstention and 1 point for guessing correctly. SWE-bench requires the model to fix code vulnerabilities on GitHub, with 0 point for submitting a wrong patch and 0 point for submitting “I can’t fix it.” So the model will forcefully output a seemingly working patch even if it has bugs.

The paper uses a simple mathematical derivation to prove that under a binary scoring system, no matter how low the model’s confidence in an answer, “guessing” is always the optimal choice.

Suppose the model is only 10% confident in an answer. Then the expected score of “guessing” is 10%×1 + 90%×0 = 0.1, while the score of “abstention” is 0. Obviously, guessing is more cost-effective. Even if the model is only 1% confident, the expected score is 0.01, still higher than 0. Therefore, under the incentive of binary scoring, the model will prioritize “outputting an answer” rather than “admitting it doesn’t know,” even if this answer is made up.

The Model Performance Thought Experiment

The paper also did a thought experiment: suppose there are two models, Model A and Model B. Model A is honest: it answers what it knows and says “I don’t know” when it doesn’t, never hallucinating. Model B is the opposite: it makes up a seemingly reasonable answer when it doesn’t know, often hallucinating.

Which model scores higher on existing evaluation benchmarks?

The answer is Model B. Because among the questions in existing benchmarks, there is always a part that Model A doesn’t know but Model B can “guess correctly.”

For example, in 100 questions, Model A knows 60, answers 60 correctly, and abstains from 40, with a total score of 60. Model B knows 60, answers 60 correctly, and guesses 10 correctly out of the remaining 40, with a total score of 70. Although Model B has 30 hallucinations, its score is higher.

And when vendors optimize models, they only look at “benchmark scores,” not “hallucination rates,” which leads the model to gradually abandon “honestly expressing uncertainty” and instead learn “how to guess better” during post-training, with the hallucination rate remaining high.

The Limitations of Model Referees

What’s more, many evaluation benchmarks use “models as referees” to score. For example, Omni-MATH lets the model output the problem-solving process and then lets another model judge “whether the process is correct.”

But the paper points out that model referees often judge “incorrect but lengthy problem-solving processes” as correct because they “look professional.” This further encourages the model to “create detailed error content” rather than “simply admitting it can’t.” For example, in a math problem, Model A says “I don’t know” and gets 0 point. Model B makes up a lengthy derivation full of formulas. The model referee doesn’t notice and even gives 1 point. This “miscarriage of justice” will make the hallucination problem worse.

Many researchers have tried to solve the problem by “adding special hallucination evaluation benchmarks,” but the paper thinks this is useless because the influence of existing mainstream benchmarks is far greater than these new ones. Vendors will still prioritize optimizing benchmark scores rather than hallucination evaluation scores.

It’s like in a school, a so-called “honesty exam” is added, but college entrance examinations and high school examinations still only look at scores. Students will still guess in college entrance examinations and will not give up scoring opportunities just because of the “honesty exam.” The paper calls this phenomenon “the epidemic of penalizing uncertainty.”

Recommendations for Improvement

To solve it, we cannot just rely on adding new evaluations, but need to modify the scoring logic of existing mainstream evaluations to give reasonable points for honestly expressing uncertainty.

Although the core of hallucinations is pre-training statistical errors and post-training evaluation misalignment, the solutions should also start from these two points. The paper doesn’t propose complex technologies, but gives two simple yet fundamental suggestions: “explicitly specify confidence targets in evaluations” and “modify the scoring logic of mainstream evaluations.”

Implementing Confidence Targets in Evaluations

The paper suggests adding to the evaluation prompts to explicitly tell the model “when to answer and when to abstain.”

For example, add a sentence after the question: “Only answer when your confidence in the answer exceeds 90%. Correct gets 1 point, wrong deducts 9 points, saying ‘I don’t know’ gets 0 point.”

Why is this effective? We can calculate: if the model’s confidence is 90%, then the expected score for “answering” is 90%×1 + 10%×(-9) = 0.9 - 0.9 = 0, same as “abstention.” If confidence is 91%, the expected score is 0.91 - 0.09×9 = 0.91 - 0.81 = 0.1, higher than abstention. If confidence is 89%, the expected score is 0.89 - 0.11×9 = 0.89 - 0.99 = -0.1, lower than abstention. This way, the model will automatically “answer” when confidence >90%, otherwise abstain, without blindly guessing.

Adjustments in Post-training Scoring Logic

The paper mentions several commonly used confidence thresholds: t=0.5 (wrong deducts 1 point, correct gets 1 point), t=0.75 (wrong deducts 2 points), and t=0.9 (wrong deducts 9 points). Different thresholds correspond to different application scenarios. For example, the medical field needs high thresholds like t=0.99 to avoid wrong diagnoses, while daily conversations can use low thresholds like t=0.5 to allow occasional small errors.

More importantly, “explicit confidence targets” need to be written in the prompts to let the model clearly know the “scoring rules.” Previous research has also tried “penalizing errors,” but most didn’t explicitly tell the model “the penalty strength,” causing the model to be unable to judge “whether to take the risk or abstain.”

The paper gives an example: after adding “wrong deducts 2 points” to the prompt, the model’s hallucination rate decreased by 30%, while the correct answer rate did not decrease significantly. This shows that the model is fully capable of adjusting behavior according to scoring rules, it just didn’t get clear instructions before.

For post-training, the paper emphasizes that the key to solving hallucination problems is not to add “hallucination evaluations,” but to integrate “confidence targets” into existing mainstream evaluation benchmarks.

For example, SWE-bench can modify its scoring rules to “get 1 point for submitting a correct patch, deduct 2 points for submitting a wrong patch, and get 0 point for submitting ‘cannot fix’.” MMLU-Pro can add an “I don’t know” option that gets 0.2 points instead of 0.

Why modify mainstream evaluation benchmarks? Because they are the “baton” that guides vendors to optimize models. If these evaluations are not modified, even if 100 “hallucination evaluations” are added, vendors will not prioritize optimizing them because mainstream benchmark scores directly affect the market competitiveness of the model.

For example, one model scores 80 on MMLU with a 50% hallucination rate, another scores 75 on MMLU with a 10% hallucination rate; vendors will most likely choose the former because customers value MMLU scores more.

Drawing Parallels with Human Examination Reforms

The paper also mentions an interesting phenomenon: that human tests have undergone similar reforms. For example, American SAT and GRE exams used to have “no penalty for wrong answers,” leading students to blindly guess. Later they changed to “deduct 0.25 points for wrong answers,” so students would give up guessing when they were “not sure.”

Therefore, large model evaluations should also learn from this approach and guide models from “test-taking machines” to “trustworthy assistants” by adjusting scoring rules.

Understanding Behavioral Calibration

In addition, the paper proposes the concept of “behavioral calibration.” It doesn’t require the model to output “I’m 90% confident” but requires the model to “output answers when confidence > t, otherwise abstain.” This calibration can be verified by comparing correct and abstention rates across different thresholds.

For example, at t=0.9, the model’s correct answer rate should be ≥90%, and the abstention rate should correspond to the proportion of questions it’s “not sure about.” Most existing models haven’t undergone this calibration, but the paper believes this will become an important indicator for evaluating large language models in the future.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although the analysis in this paper is very profound, it also admits that there are still some limitations in the existing framework that need further research to improve. First, the paper only considers “reasonable wrong content” and ignores “nonsense content,” like the model outputting “afbsehikl” as gibberish.

But in reality, existing models rarely output nonsense content because their pre-training objective is to “generate reasonable language,” so this limitation doesn’t affect the conclusion much.

Second, the paper mainly analyzes “factual questions” with less discussion on “open-ended generation” hallucinations. Hallucinations in open-ended generation are harder to quantify, for example, 1 error vs. 10 errors in a biography clearly indicate different levels of hallucination, but the paper’s framework doesn’t distinguish this “degree difference.”

In the future, a “hallucination level scoring system” may need to be established instead of a simple “correct/wrong” binary division.

Third, the paper points out that “retrieval-augmentation (RAG) is not a panacea.” Many people believe that adding a “search engine” to the model to let it look up information before answering can eliminate hallucinations. But the paper believes that RAG can only solve “facts not in the training data” but cannot solve situations where “information cannot be retrieved.”

For example, if a scholar’s birthday cannot be retrieved, the model will still make up a date because existing evaluations encourage guessing. Only combining “retrieval + confidence targets” can completely solve the problem: answer when information is retrieved and confidence > t, abstain when information cannot be retrieved or confidence < t.

Fourth, the paper does not consider the problem of “potential context ambiguity.”

For example, when a user asks “My telephone is broken, what should I do?,” this “telephone” could mean “cellphone” or “land line,” but the prompt doesn’t specify. In this case, the model’s error is not “hallucination” but “misunderstanding,” but the existing framework cannot distinguish between these two situations.

In the future, “user’s potential intent” may need to be included in error analysis to let the model learn to “ask follow-up questions” rather than answer blindly.

Conclusion

Alright, that’s the main content of this paper. The biggest inspiration I got is that AI problems are often not technical problems but “human problems.” What kind of training objectives we design will determine what kind of model we get; what kind of evaluation rules we design will guide the model in what direction.

To solve hallucination problems, we need not only to optimize the model but also to optimize our “expectations and evaluation methods for AI.”

After all, we need a “truly trustworthy assistant,” not just a “straight-A student.”

References

- Why language models hallucinate OpenAI. 2025-09-05

- Why language models hallucinate - pdf OpenAI. 2025-09-05

- Omni-MATH Omni-MATH.