12-Factor Agents: Mastering Production‑Ready AI Design

Believe that friends in the AI industry would have the feeling that agents are moving from concept to realization. But moving from “able to run” to “able to be used stably” still has a huge gap. Today I want to talk about the “12‑Factor Agents, created to bridge that gap.

It should be noted that this set of factors is not a toolbox like LangChain that can be directly used. It is a methodology, like the “12‑Factor App” factors in software development a long time ago. It creatively applied best practices proven in traditional software engineering to large‑model‑driven agent development. Its core goal is also clear: to bridge the gap from prototype development to production‑grade applications, so that agents meet enterprise standards in reliability, scalability, maintainability, debuggability, and security.

Before diving into the twelve factors, we need a little time to introduce some background related to this project.

Origin and Vision

The initiator of the 12‑Factor Agents project is a San Francisco startup called HumanLayer. Its founder is Dexter Horthy. His experience is interesting: at 17 he started programming at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Later he spent 7 years at a dev‑tool company Replicated, moving from engineer to product manager to executive, delivering local K8s products for companies like HashiCorp and DataStax. That experience gave him a deep understanding of “production‑grade systems,” because the reliability of distributed systems and the scalability of container orchestration are the daily issues he faced.

What really turned him toward the agent field was a 2023 project. At that time he was building a Slack‑based agent to manage SQL databases. During development he discovered a key problem that many ignore: how can an agent effectively bring humans “in the loop” when executing tasks? For example, when an agent needs to run a potentially production‑impacting SQL statement, it cannot decide on its own; it must get human approval. But traditional agent designs keep humans sitting at a screen, waiting for the AI to speak; the AI doesn’t proactively ask for feedback.

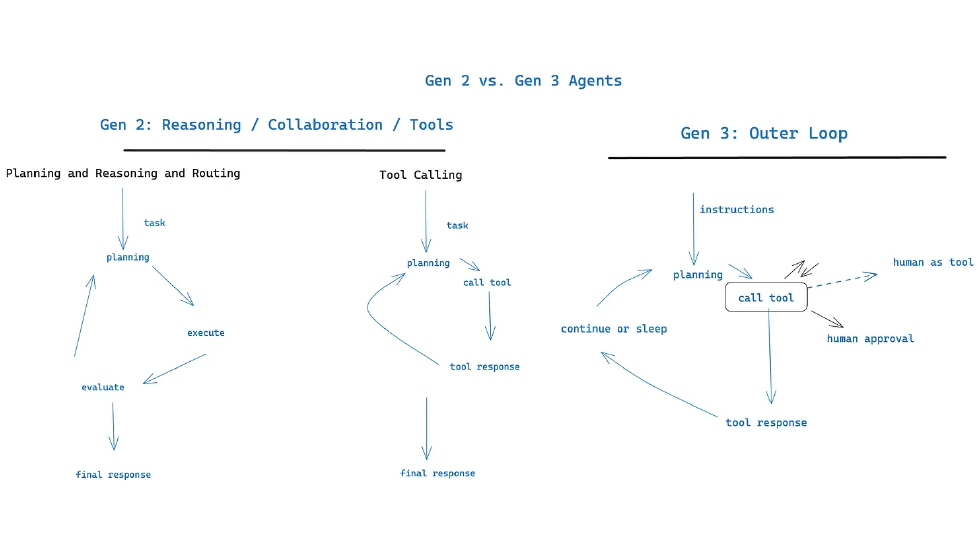

This “Human‑in‑the‑Loop” pain point not only led him to found HumanLayer but directly gave rise to the core idea of 12‑Factor Agents. Horthy’s vision is to push agents from the first‑generation question‑answer chat, through the second‑generation framework‑driven agents, to a third‑generation autonomous agent that does what it can on its own and asks for help when it can’t—efficient and safe.

Core Idea of HumanLayer

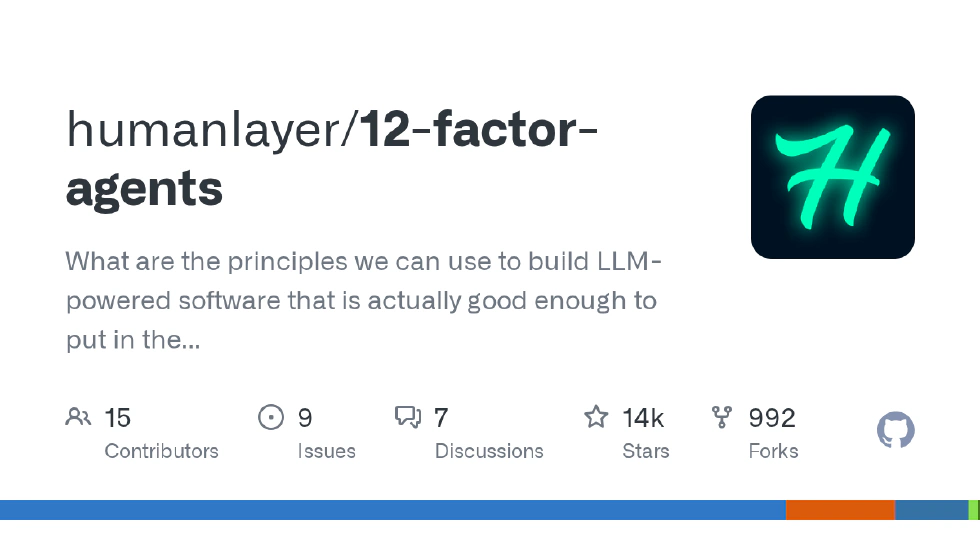

After the background, let’s look at the 12‑Factor Agents project itself. Currently it has 14k stars and 992 forks on GitHub. Its code is primarily written in TypeScript with a small amount of Python.

The core innovation of the whole project is its “anti‑framework” concept. Unlike traditional frameworks, it does not provide a black‑box solution. It insists on letting developers have full control of the core components. Why design it this way? In enterprise applications, transparency, debuggability, and maintainability are more important than “how fast you can develop.” For example, a financial agent developer must know every step of the logic, what data flows where, and cannot hand the core logic over to a framework’s black box.

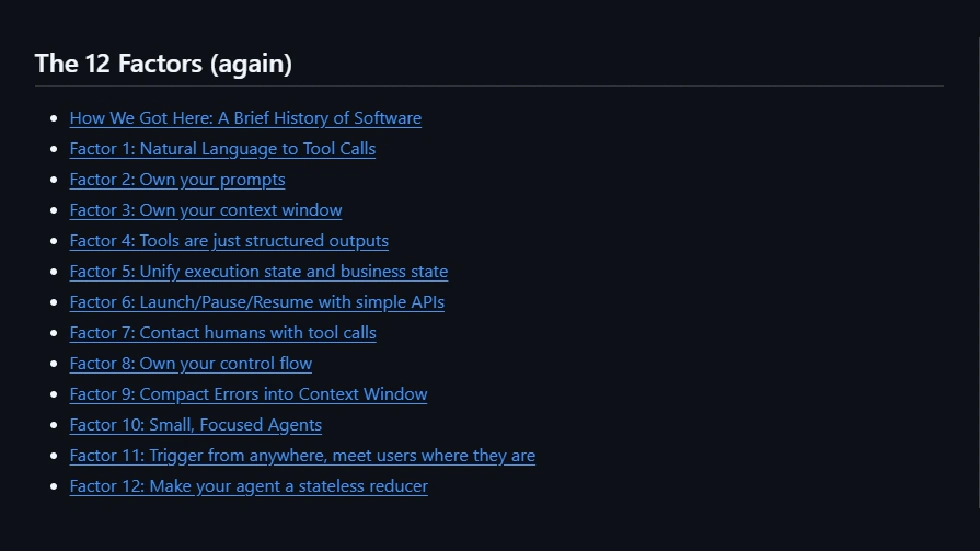

Now we will dissect the twelve design factors, each corresponding to a key requirement for production‑grade agents. I’ll explain what they are, why they matter, and how to implement them.

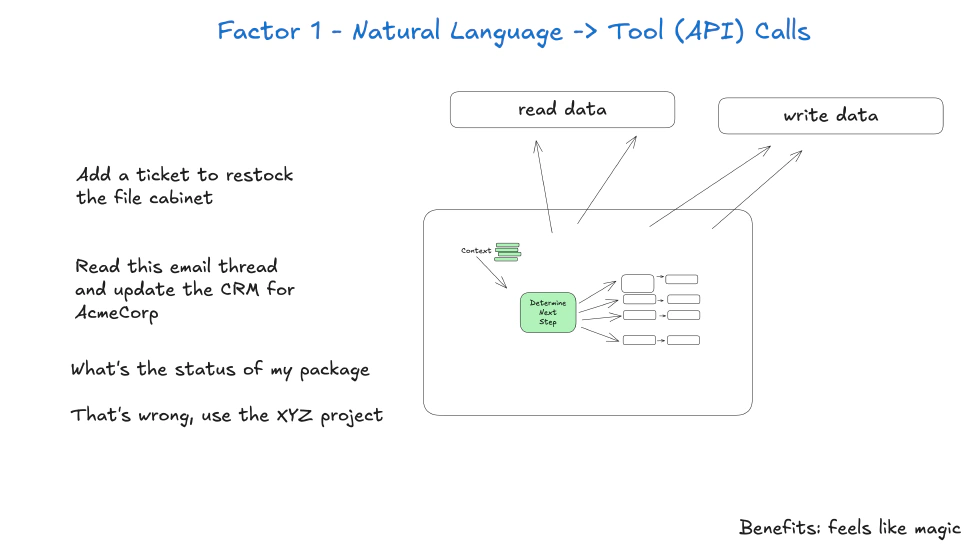

Factor 1: Natural Language to Tool Calls

The core of this factor is that an agent’s main capability should be converting human natural‑language instructions into structured tool calls, rather than directly “answering questions.” After understanding the problem, the agent should invoke appropriate tools.

For example, if a user says, “Please look up last month’s sales total,” the agent should not just spit out a number. Instead, it should transform the utterance into two structured tool calls: first call the “sales‑data‑query tool” with parameter “date_range: last month”; second call the “Excel‑generation tool” with parameter “source data: sales‑query result.” Why is this important? Natural language is fuzzy, but tool calls are precise. Structured tool calls make the agent’s behavior predictable and make debugging easier. For instance, if no report is generated, a developer can check whether “the parameters were wrong,” not guess whether the agent misunderstood natural language.

The key to implementing this factor is designing clear tool interfaces: each tool’s function, required and optional parameters, return fields—all must be explicitly defined so the large language model can call them accurately.

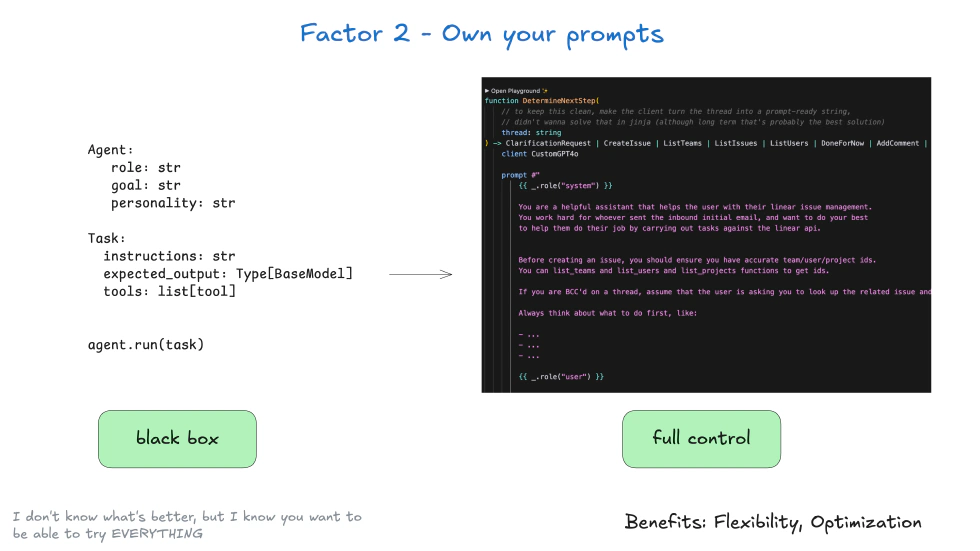

Factor 2: Own Your Prompts

Prompts are the soul of large‑model applications, but many frameworks hide them inside. For example, with LangChain you can’t see the prompt sent to the model. This factor stresses that developers must fully control prompt design, modification, and versioning.

Why “own prompts”? Because different business scenarios need different prompts. A customer‑service agent for electronics versus apparel will have different tone and product knowledge. If the prompt is hidden inside the framework, developers cannot adjust the agent’s performance to match business needs, diminishing effectiveness.

Moreover, prompt version control is vital in production. If a modified prompt lowers accuracy, you need to roll back. To implement this factor, treat prompts as “code”: keep them in a repository, version‑control them, and even run A/B tests. For example, you can run two prompt versions in parallel to discover which yields higher tool‑call accuracy, then choose the better one.

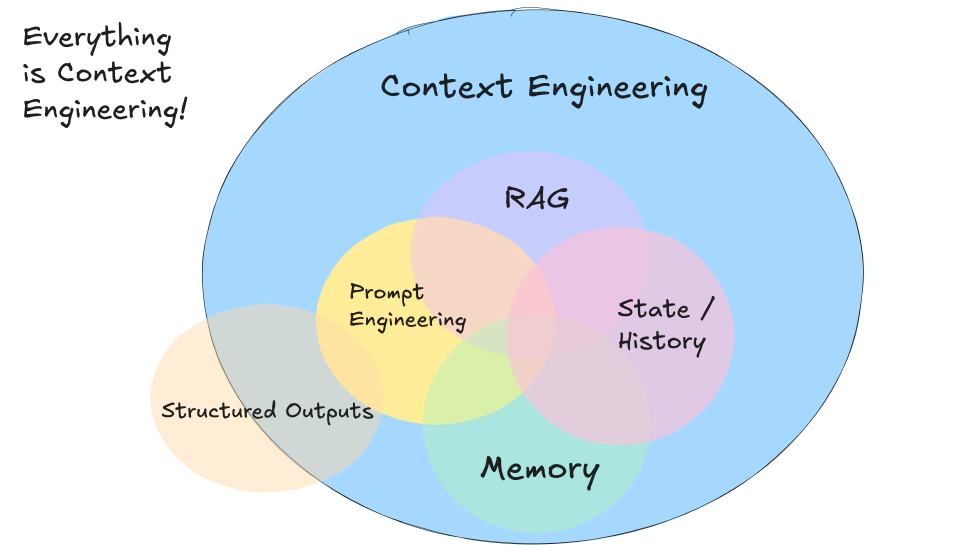

Factor 3: Own Your Context Window

The context window of a large model is finite, and how you manage it directly influences agent performance. The core of this factor is that the framework should not decide what stays in context and what is discarded. Developers must control context‑window management logic.

For example, for an agent processing a long conversation, the context window may approach capacity. What do you drop? The earliest dialog, repeated information, or unimportant details? Different scenarios require different rules. In customer‑service chat you may keep the core user request such as “needs a refund” while removing unrelated chatter. In technical support you might keep referenced error messages and drop redundant product descriptions. If the framework arbitrarily deletes the oldest dialog, the agent might forget the user’s core request, leading to false decisions.

Therefore, developers should design context‑management logic based on “information importance” ranking: keep key information, drop secondary. To implement this, developers need a scoring schema: user needs, critical system parameters, tool‑call results are high importance; politeness, repeated questions low importance. You can then prune accordingly.

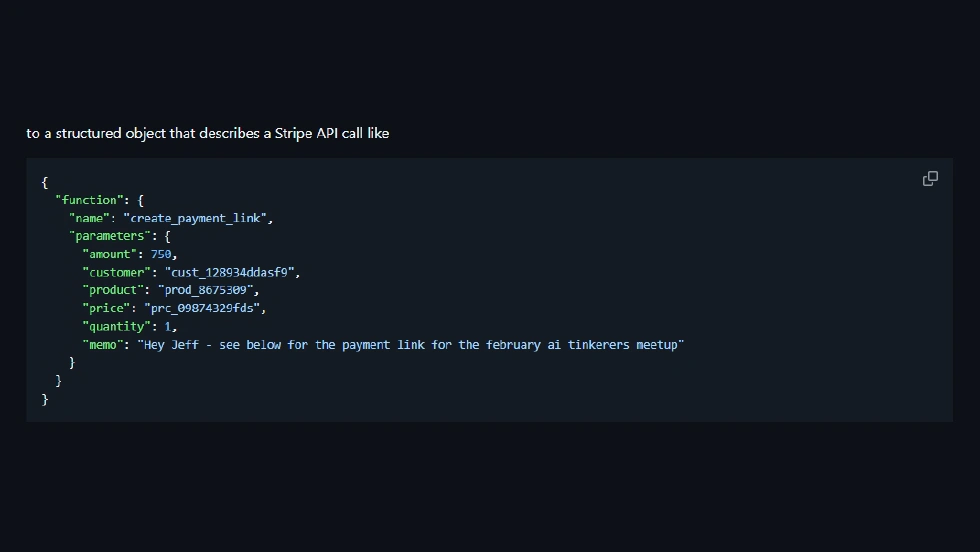

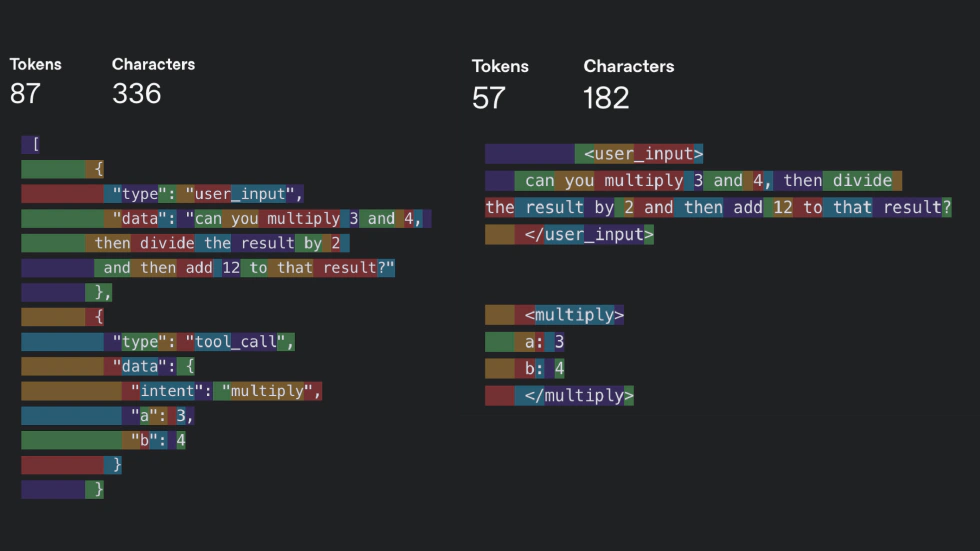

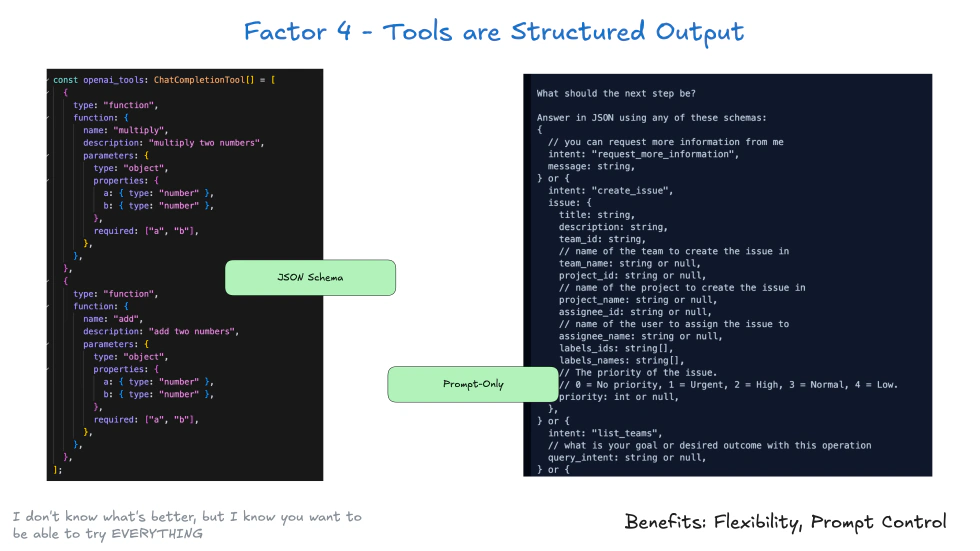

Factor 4: Tools Are Just Structured Outputs

This factor may feel counterintuitive. It treats “tool calls” as a structured output of the model, not as the agent physically invoking an external tool.

For example, instead of outputting “call sales‑data‑query tool,” the model outputs JSON‑formatted structured data. Why think this way? It simplifies system architecture. The agent doesn’t need to know “how to call the tool”; it just outputs structured instructions. A dedicated “tool‑execution module” then parses that instruction and calls the corresponding tool. This separation makes the system easier to maintain. If the sales‑data‑query tool’s interface changes, you only change the tool‑execution module, not the agent logic. Adding a new tool is simply adding new implementation in the execution module; the agent continues outputting the corresponding structured instruction.

Implementation: standardize the call format. For example, all tool calls use JSON with two fields: tool_name and arguments. The execution module can then parse uniformly.

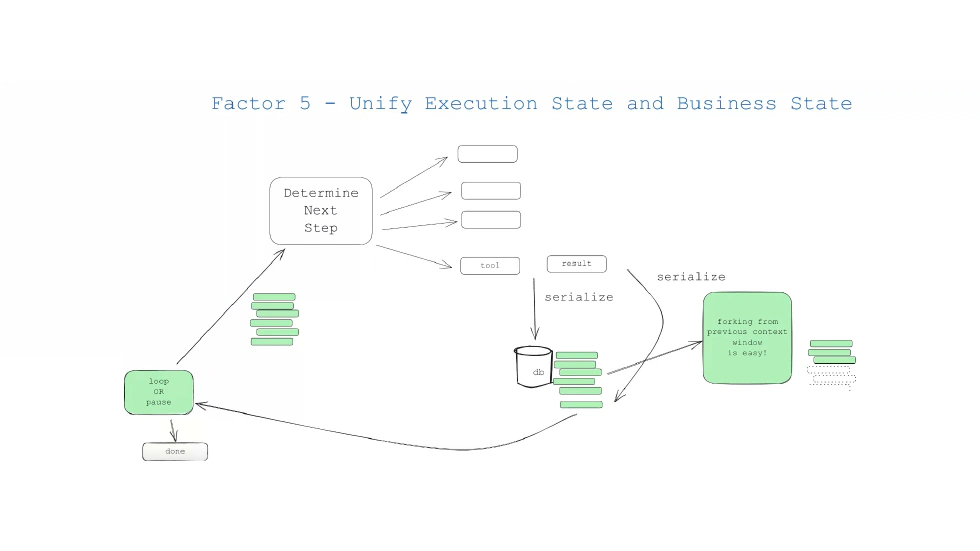

Factor 5: Unify Execution State and Business State

In traditional agent design, execution state (e.g., “calling tool” or “awaiting user feedback”) and business state (e.g., “order number” or “sales‑query result”) are usually separated; the former in memory, the latter in a database. This separation easily causes “state inconsistency”: the agent may believe it has called a tool, but the tool actually failed, so the business state isn’t updated, leading to erroneous subsequent actions.

The core of this factor is to manage execution state and business state together as a unified “global state.” For example, the global state includes the current step waiting for a tool result (execution state), the parameters used in the tool call, and the tool’s return result (business state). The benefit: if an agent crashes—for instance, after calling a tool but before processing the result—it can restart and recover from the global state, knowing exactly which step it left off, what parameters were used, and what results it still needs to handle. This removes the need to restart from scratch.

Implementation: use a dedicated state‑storage service such as Redis or a database to hold the global state. Each agent task has a unique ID; you query the global state via that ID.

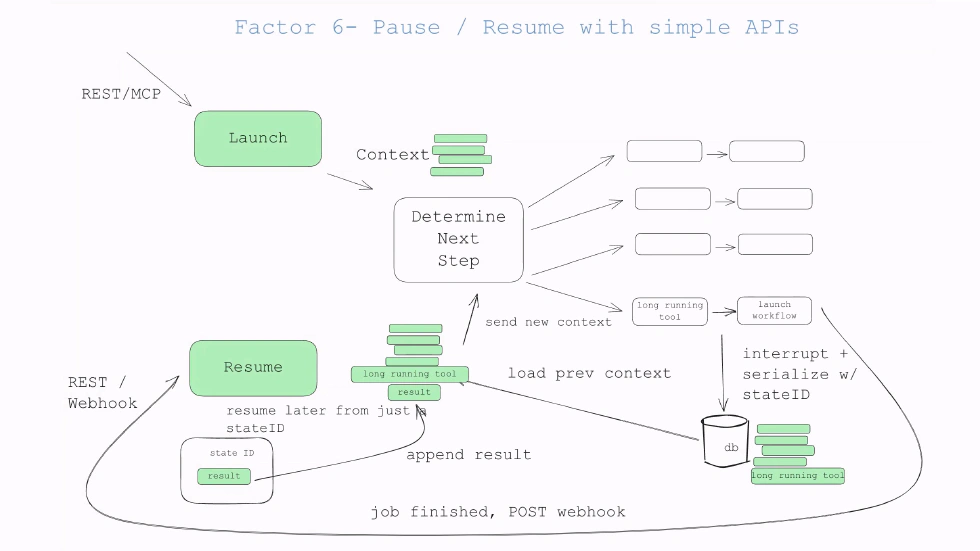

Factor 6: Launch/Pause/Resume with Simple APIs

In production, agents may need to handle long‑running tasks—generating an annual sales report may call multiple tools and process large amounts of data, taking hours. If the task fails or needs pausing, you need simple APIs to control. The core of this factor is that start, pause, and resume should all be accessible via straightforward APIs, not by modifying code or config.

For example, POST /agent/start to launch a task, POST /agent/pause?task_id=xxx to pause. Why simple API? In production, operations personnel may use automation tools to batch pause or resume many agents; the APIs must be simple and robust. Implementation: design RESTful APIs, specifying parameters, return values, and error handling. For “pause” API, if the task is already paused, return 400 Bad Request with message “Task is already paused.”

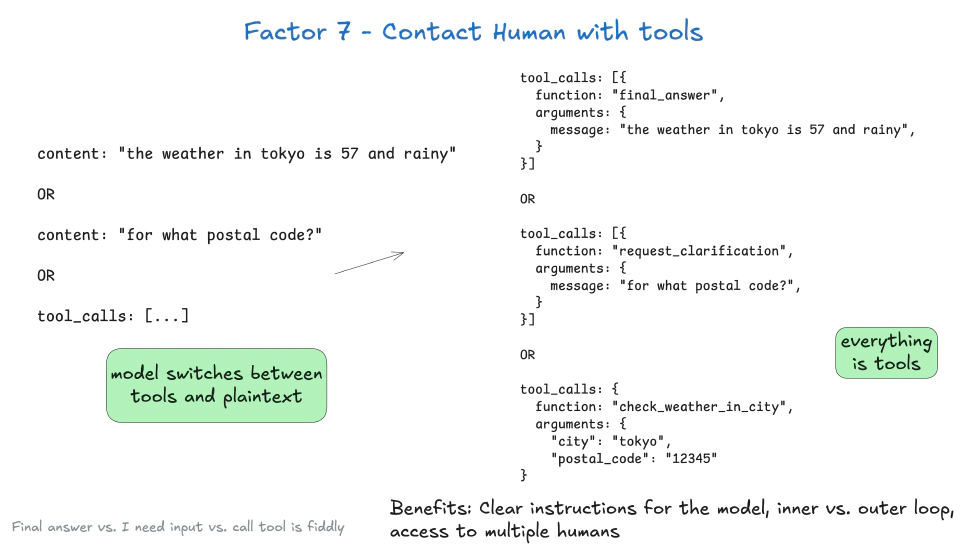

Factor 7: Contact Humans with Tool Calls

This is the most innovative factor among the twelve. It makes agents proactively contact humans via “human‑tool calls” to get feedback instead of waiting for humans to latch on. The “human‑tool” can be a tool dedicated to human interaction, e.g., “send approval notification” or “get human feedback.”

For example, an agent wanting to execute a SQL change first calls “send approval notification” with parameters like “content: execute SQL xxx; approver: DB admin.” Once the admin approves, the agent calls “get human feedback” to receive “approval granted” and then proceeds.

Traditional human‑machine interaction is “human to AI”; this flips it to “AI to human,” making the agent initiate interaction while humans respond passively. This fits production because humans don’t need to watch the agent constantly; the agent reaches out only when it needs human input, efficient and safe.

To implement, design dedicated “human‑interaction tools,” e.g., integrate corporate WeChat, Slack, email, etc., so the agent can notify humans. Also design feedback collection mechanisms: after a human clicks “approve” or “reject,” the feedback automatically returns to the agent’s global state.

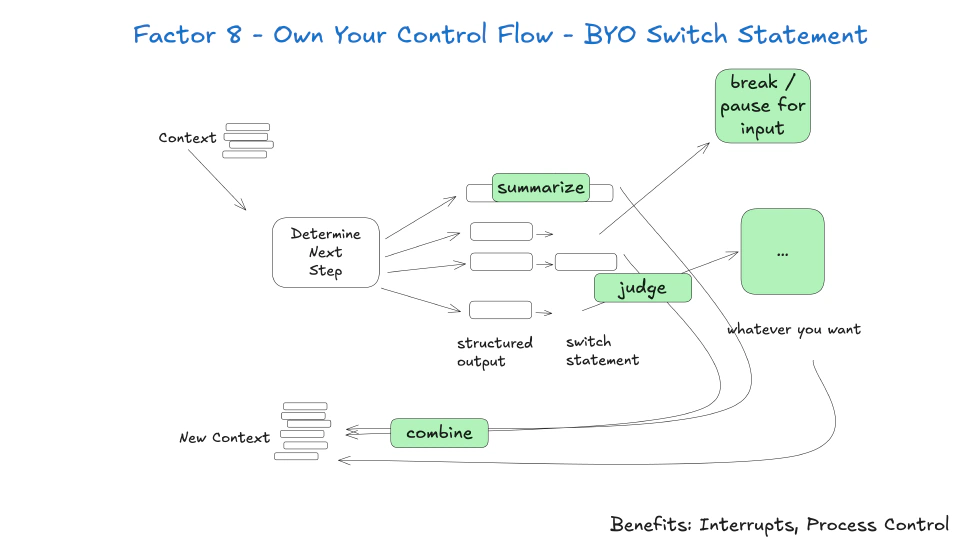

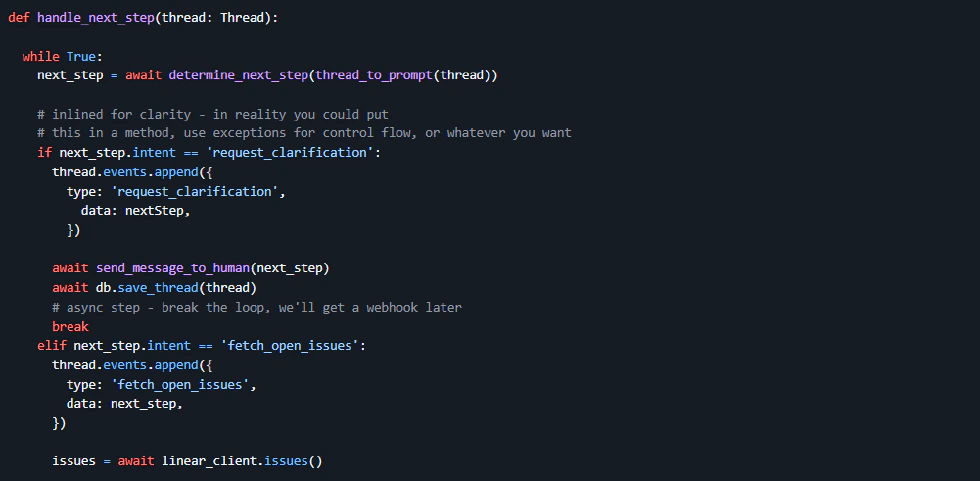

Factor 8: Own Your Control Flow

Control flow is the agent’s execution logic, e.g., first call tool A, then depending on tool A’s result decide to call tool B or C. The core of this factor is that developers must fully own control flow, not let the framework decide.

Many frameworks provide predefined flow patterns like a sequential chain or conditional branch chain. But enterprise logic can be complex: a supply‑chain agent may first query inventory; if inventory is sufficient, ship; if insufficient, purchase, then ship; while also handling purchase failures, perhaps notifying the procurement manager. The framework’s default flow may not cover such complexity, or editing it later would be difficult. Therefore, developers must design control flow themselves, e.g., code the exact sequence and conditions.

To implement, use a state‑machine approach. Each state represents an agent execution step; transitions are triggered by conditions. For example, a “inventory‑query‑complete” state could transition to “ship” or “purchase” or “notify‑failure,” depending on result. This keeps logic clear and extensible.

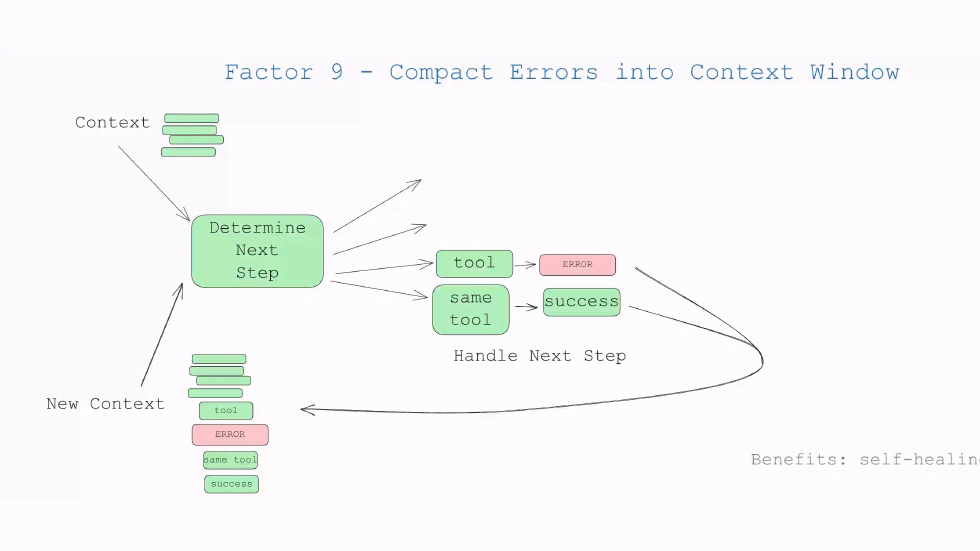

Factor 9: Compact Errors Into Context Window

Agents inevitably fail in production: tool calls may fail, the model may return errors, or parameters may be ill‑formed. The core of this factor is to compress error information into a compact form that fits into the model’s context window so the model can adjust its behavior.

For example, if the sales‑data‑query tool returns an error because the “time_range” parameter format is wrong, the agent should compress the error into the context window and then regenerate a tool call. The compacted error contains key details: error type, reason, maybe a short fix suggestion.

Why compact? Because the context window is limited; a long stack trace would consume a lot of space, pushing other important data out. Therefore, error messages need to be distilled into key info before inclusion.

To implement, design error‑compression logic. Extract error type, source, cause, and a concise remedy; drop irrelevant stack trace or log IDs.

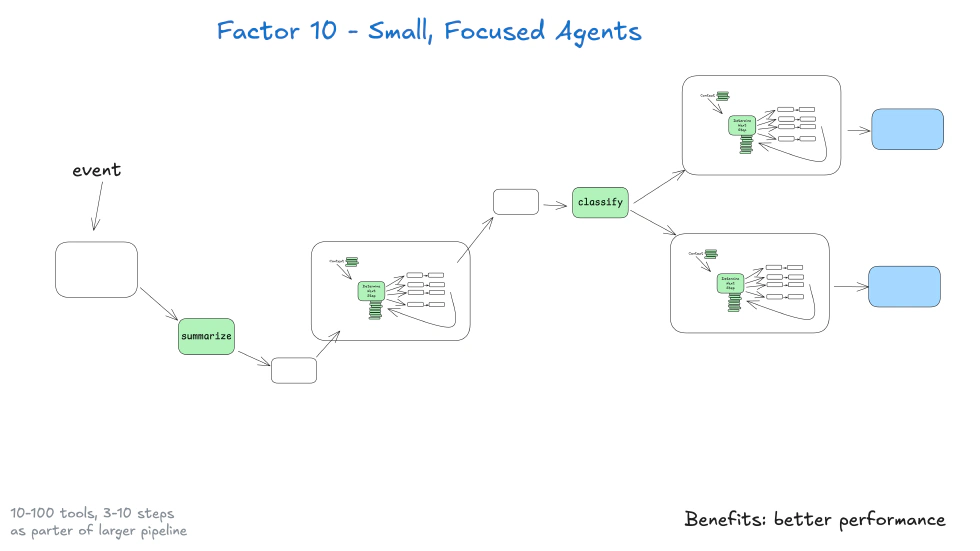

Factor 10: Small Focused Agents

This factor borrows from microservices. Instead of building a “super‑agent” that can do anything, build multiple small focused agents, each responsible for a specific domain.

For instance, split the “enterprise‑management agent” into a “sales‑data agent” (query, analyze sales data), a “inventory‑management agent” (query inventory, trigger purchase), a “customer‑service agent” (handle queries). Each focuses on its domain, leading to simpler logic and easier maintenance.

Why small focused? Super agents are too complex, prone to errors, harder to debug. With small agents, you can debug by looking at the relevant code only. Also, it facilitates team division: sales can maintain the sales‑data agent; inventory can maintain inventory‑management agent, etc.

To implement, achieve domain decomposition. Each agent’s input, output, tool calls are clear, preventing overlap. For example, sales agent outputs a “sales report” used by inventory agent as input; they communicate via structured data, not shared internal logic.

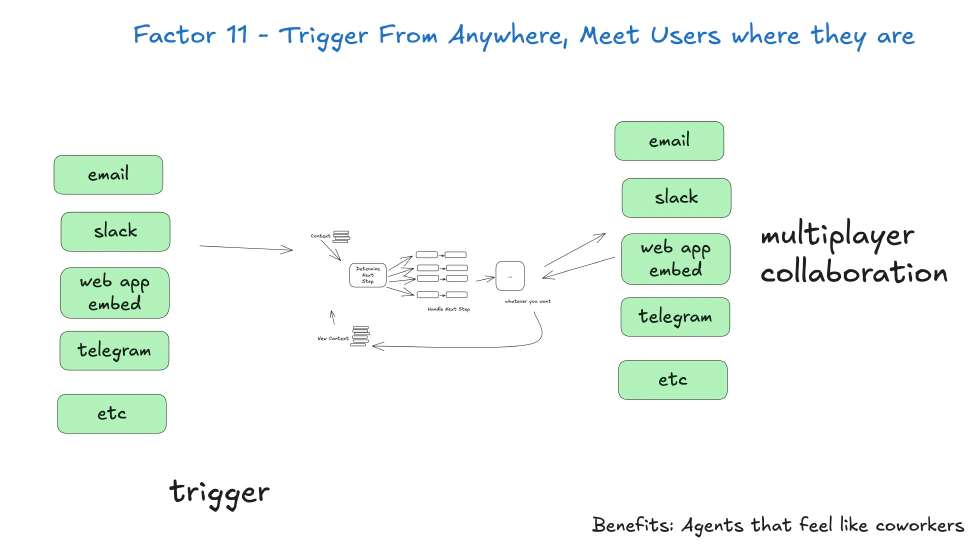

Factor 11: Trigger From Anywhere

Enterprise systems are diverse: Slack, corporate WeChat, CRM, ERP, scheduled jobs, webhooks, etc. This factor says that agents should be triggered from any of these sources, not just a fixed interface.

For example, the sales data agent can be triggered by: (1) an operator issuing “query last month’s sales” in Slack; (2) a CRM event where an order exceeds 1 million triggers automatic report generation; (3) a weekly 8 a.m. scheduled task triggers weekly report generation.

Why trigger from anywhere? So agents integrate into existing workflows, not the other way around. Operators using Slack don’t need to lift the app, etc.

To implement, design trigger adapters for each source. Each adapter listens to its source (Slack adapter listens to Slack messages, CRM adapter listens to CRM events, scheduler adapter triggers on time). All adapters output a uniform “trigger command,” so the agent doesn’t care where it came from.

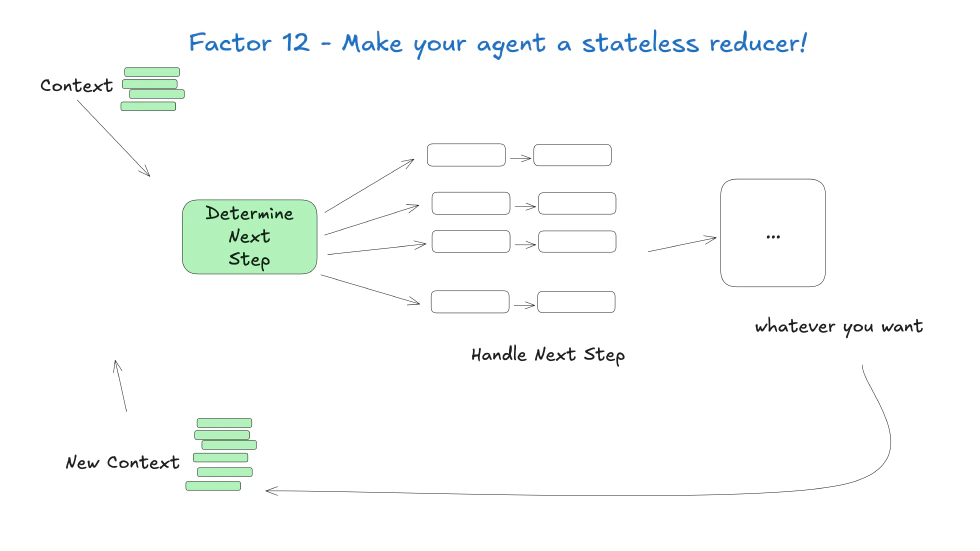

Factor 12: Make Your Agent a Stateless Reducer

Inspired by functional programming’s “reducer” concept: the agent is stateless; its behavior depends only on “current input” and “external state,” not internal memory. A reducer receives current state and input, processes, outputs new state.

For example, the agent receives a state that it has called the sales‑data query tool but hasn’t generated a report. The input is the sales‑data result 1 million. The output is a state that report is generated, awaiting delivery to the operator.

Why stateless? Stateless agents are easier to scale. If 100 users trigger the sales data agent, the server can spin up 100 agent instances, each processing a user separately, no shared state. If an instance crashes, others are unaffected; a new instance can resume from external state.

To implement, keep all state externally. The agent retrieves the external state at the start, processes, writes the new state back, then releases resources. So the agent never stores state internally.

Interdependence of the 2‑Factor Agents

These twelve factors aren’t isolated; they work together. For example, the stateless reducer (Factor 12) relies on unified execution and business state (Factor 5). The ability to trigger from anywhere (Factor 11) depends on the natural‑language‑to‑tool‑call conversion (Factor 1). The human‑tool‑call factor (Factor 7) requires small focused agents (Factor 10) to reduce complexity. Together they form a complete production‑grade agent design system that addresses reliability, scalability, maintainability, etc.

The Role of 12‑Factor Agents Amid Frameworks

Many may ask, with frameworks like LangChain, LlamaIndex, AutoGen, why still need 12‑Factor Agents? The answer: they’re not competitors but complementary. 12‑Factor Agents are “design factors,” frameworks are “implementation tools.” The factors guide how to use the tools.

Simply put, 12‑Factor Agents are the coach, telling the team how to win; frameworks are the players executing the tactics. You can use LangChain to build an agent, but you must follow 12‑Factor Agency factors: own prompts (Factor 2), own context windows (Factor 3), unify state (Factor 5), etc. Then you get production‑grade agents.

So 12‑Factor Agents don’t replace frameworks; they maximize their value. Many developers build prototypes with frameworks quickly, but problems arise in production—often because engineering practices aren’t followed. 12‑Factor Agents fill that gap, turning prototype tools into production tools.

A Mindset Shift for Production‑Ready Agent Engineering

For those working in agent development, the inspiration from 12‑Factor Agents goes beyond technical details; it’s a mindset.

First, a “design‑thinking shift”: from pursuing rapid prototyping to emphasizing production quality. Previously we may think “first make it run, then refine.” Now realize that in production, stability beats speed. Investing in prompt design, control flow, state management up front saves debugging time later.

Second, a heightened “architecture awareness”: don’t focus only on model tuning and prompt optimization; also consider system architecture—state storage, tool decoupling, error recovery—those are key to whether an agent can be deployed.

Third, “user‑experience innovation”: don’t limit to chat interface; think how an agent can proactively integrate into users’ workflows, e.g., alerting a customer‑service rep that a client has a refund record. That proactive collaboration is the agent’s core value.

Fourth, “interdisciplinary integration”: agent development isn’t purely AI; it requires distributed systems, DevOps, product design, etc. Knowledge of stateless design, fault tolerance, CI/CD, monitoring, and user‑journey tactics all help build a robust agent.

Conclusion

Finally, I quote a line from HumanLayer: “Don’t repeat the pitfalls of early software development; start with solid engineering culture and design factors from the beginning.” Agents are crucial vehicles for AI delivery; 12‑Factor Agents are the key step to making them “good” and “stable.”

References

- The Twelve-Factor App The Twelve-Factor App.

- Startups F24 // AI and beyond Medium. 2024-10-12

- Slack AI and Agentforce: A Practical Guide for Teams Tanka. 2025-01-16

- AI Agents With Human In The Loop Medium. 2024-08-15

- 12-Factor Agents - Principles for building reliable LLM applications Github. 2025-07-18