Jeff Dean: From Curiosity to Google Brain Leadership in AI

If you follow artificial intelligence and computer science, then the name Jeff Dean is surely familiar to you. Not only is he one of Google’s early core engineers, but he is also the creator of the world-renowned AI research team, Google Brain. His career trajectory resembles a series of brilliant entrepreneurial ventures, constantly embracing new challenges and pushing the boundaries of technology.

If you follow artificial intelligence and computer science, then the name Jeff Dean is surely familiar to you. Not only is he one of Google’s early core engineers, but he is also the creator of the world-renowned AI research team, Google Brain. His career trajectory resembles a series of brilliant entrepreneurial ventures, constantly embracing new challenges and pushing the boundaries of technology.

Today, through a podcast interview by The Moonshot Factory, we’ll delve into Jeff Dean’s formative experiences, his early explorations with Google Brain, and his deep insights into the future development of artificial intelligence.

Early Passion for Building and Computing

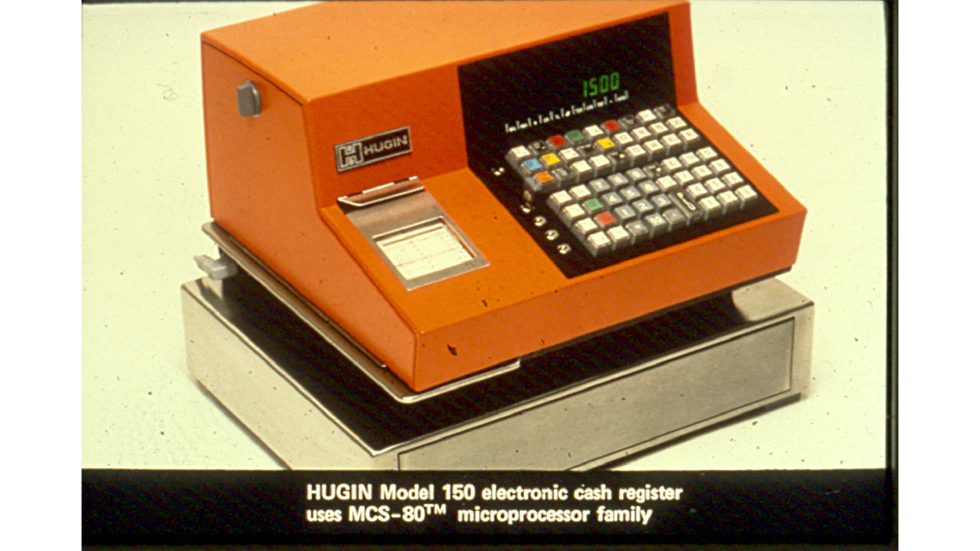

Jeff Dean’s childhood was filled with change; he moved homes 11 times in 12 years. As a child, Lego was his best companion, and building models was his greatest joy. This interest in construction shifted towards computers at age 9 due to his father’s influence. At the time, his father was a doctor who was passionate about how computers could improve public health, but mainframes had a steep learning curve.

One day, his father saw an ad in a magazine for a DIY computer kit—one you could solder and assemble yourself. This kit computer even predated the launch of the Apple II. At first, it was just a box with indicator lights and toggle switches; instructions were input manually by flipping switches. Later, they added a keyboard and installed a BASIC interpreter. This primitive computer opened the door to programming for young Jeff. He sat with a physical copy of “101 Computer Games in BASIC,” typing in code character by character, then modifying and playing the games. The experience of “creating, using, and playing” captivated him, making him realize the enormous potential of software for others.

Stepping into a Connected Tech World

After moving to Minnesota, Jeff entered a highly advanced technological environment. The local area provided a statewide computer system for all middle and high schools, allowing students to connect to chat rooms, interact with people across the state, and play interactive adventure games. At just thirteen or fourteen years old, Jeff found himself immersed in what was essentially “the pre-Internet Internet.” He engaged not only with other programming enthusiasts but also learned multi-user software skills by studying open-source software shared by others. Although he jokes that he’s not great at hands-on physical construction, he truly thrived in the world of software.

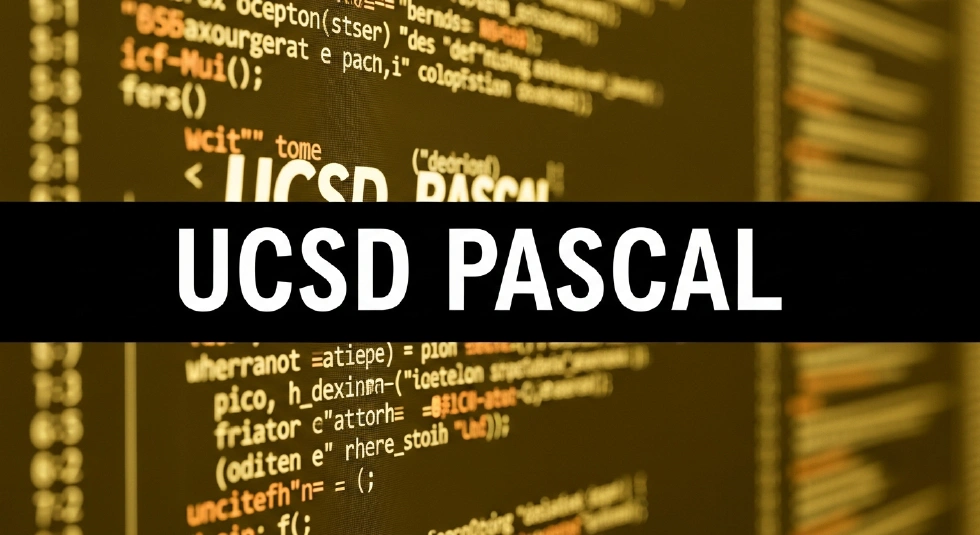

Jeff recalls writing a multi-user online game at the time, the original author being a grad student who was about to graduate. Jeff secretly used a laser printer to print all 400 pages of the source code. He then ported this multi-user software, written in Pascal for mainframes, to his family’s UCSD Pascal system. This process taught him how to handle multi-user, multi-port interrupts and how to schedule inputs from multiple terminals. Even though he was “feeling his way through the dark” at the time, this experience gave him a deep understanding of concurrent programming.

From Programming Languages to Neural Networks

When asked about his most-used programming language, Jeff readily mentioned C++. Since his work centered on distributed systems and demanded high underlying performance, C++ was a natural choice. However, he has a love-hate relationship with C++ due to its lack of safety (prone to memory leaks) compared to more modern languages.

During graduate school, his advisor—a compiler and programming language expert—invented a language called Cecil, which excelled in object-oriented methodology and modular design. They used Cecil to write a compiler supporting four languages, with the codebase reaching 100,000 lines, ultimately generating 30 million lines of C code. While Cecil’s expressiveness and standard library were excellent, sadly, its worldwide user base never exceeded 50.

Jeff Dean’s true exposure to artificial intelligence traces back to his senior year at the University of Minnesota, when he took a course on distributed and parallel programming that introduced neural networks. In the early 1990s, neural networks were exciting the academic world due to their highly parallel computation and ability to solve small, complex problems.

At the time, a three-layer neural network was already considered “deep”—whereas today, networks commonly exceed hundreds of layers. Jeff recalls that neural networks’ abstraction seemed loosely connected to our understanding of human and animal brains—artificial neurons receive inputs, assess their interest, decide whether to “activate,” and, if so, at what strength. By building many neurons in deeper layers, one can form more complex systems. Neural networks’ ability to automatically learn and extract useful features to solve pattern-matching tasks left a deep impression on him.

Inspired, Jeff approached his professor, Vipin Kumar, hoping to focus his thesis on parallel neural networks. He wanted to use the department’s 32-processor machine to train a much larger, more powerful neural network than could be done on a single processor. Quickly, however, he realized the needed computational power wasn’t 32 times greater—it was a million times more.

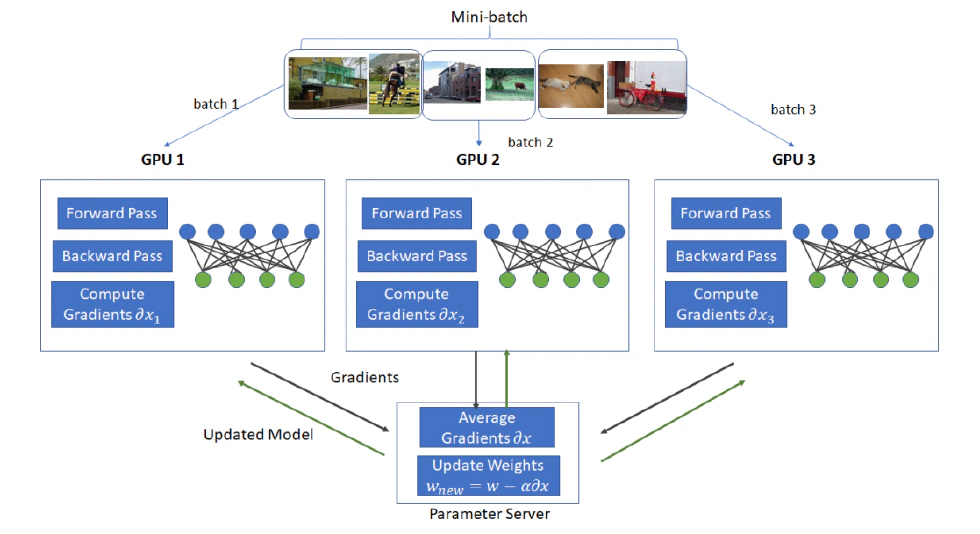

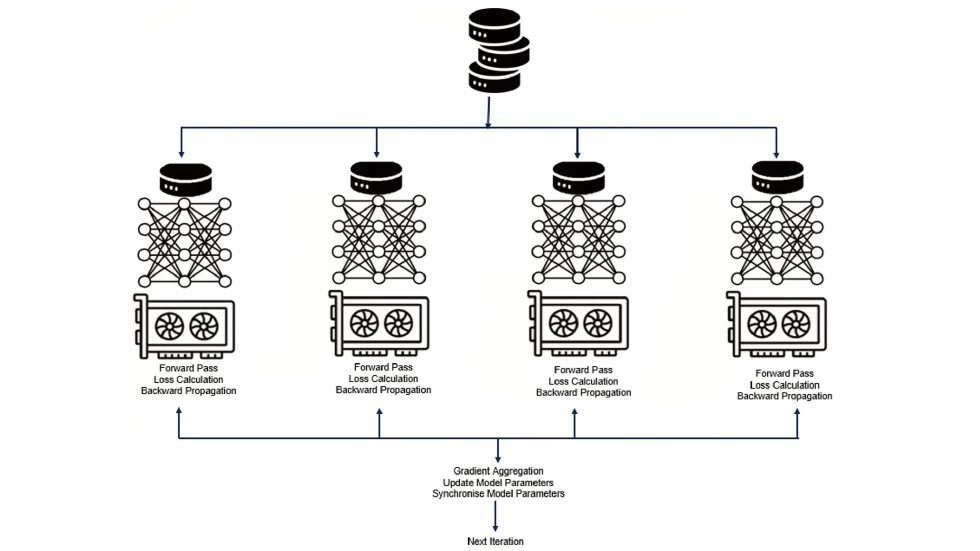

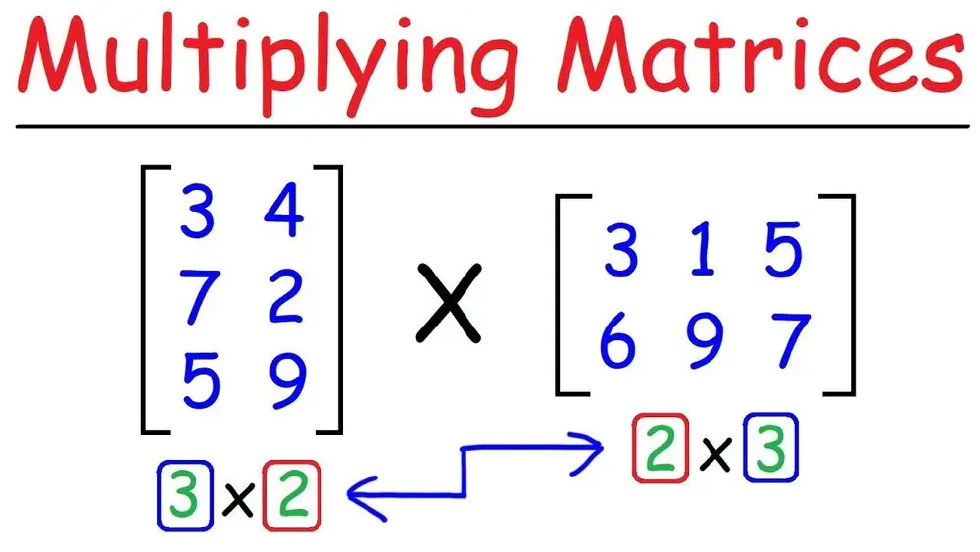

Even so, he implemented two methods for parallelizing neural network training: data parallelism (splitting input data into batches, each processor holding a copy of the network but processing only a subset of data) and model parallelism (dividing a large network into parts so all data passes through different segments of the network). These early explorations laid the groundwork for his later work at Google Brain.

Speaking of the late-90s decline in neural network popularity, Jeff admits he never truly “lost faith,” only “set it aside” for a while. He prefers to “wander between different fields”—from parallel programming to public health software to compiler design, always seeking new opportunities to learn and explore.

Working Across Disciplines and Entering Google

After graduation, he joined Digital Equipment Corporation’s R&D lab in downtown Palo Alto, working with 35 researchers on over 20 projects, from multicore processors to early handheld devices to user interface research. This environment, full of exciting intellectual exchanges and cross-domain learning, was exactly what he longed for.

Later, Jeff Dean joined Google, leaving a deep mark in information retrieval, large-scale storage systems, and machine learning applications. The launch of the Google Brain project marked another pivotal turn in his career.

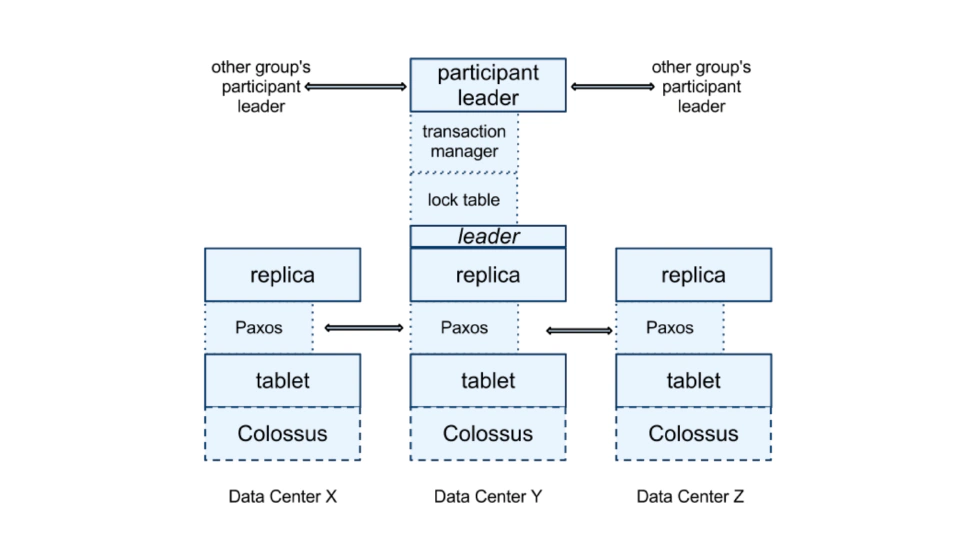

At the time, Jeff was working on Spanner—a massive storage system with excellent data consistency, aimed at unifying storage across Google’s global data centers. As Spanner stabilized and went mainstream, Jeff began pondering his next move.

By chance, he bumped into Andrew Ng in a break room. Ng, then a Stanford faculty member, spent a day each week at Google X. That serendipitous conversation became Google Brain’s “genesis.” Andrew Ng mentioned that his students had seen promising progress applying neural networks to speech and vision. Jeff was instantly interested: “Oh, really? I love neural networks! We should train truly large neural networks!” That sentiment sowed the seeds for the Google Brain team.

Andrew Ng and his students had already achieved good results using GPUs, while Jeff saw the potential of Google’s vast datacenter compute resources. He suggested building a distributed neural network training system to train enormous networks. Thus began their use of 2,000 computers and 16,000 CPU cores to train large neural networks. The team was small at first, but quickly grew as the project attracted more interest, eventually training large-scale unsupervised vision models and supervised speech models, collaborating internally with Google’s search and ads teams. Hundreds of teams ultimately used the neural network framework they first built.

The Power of Large-scale Distributed Neural Networks

Andrew Ng highly praised Jeff Dean’s contributions, noting that while Stanford students had discovered the “secret” that performance improves as neural network scale increases (the so-called “secret data”), what they lacked most was someone like Jeff, who could think at super-large scale and break down problems for distributed processing when a single machine was insufficient—skills rarely taught in academia.

Early on, many believed MapReduce would be critical to Google Brain, but as the project progressed, Jeff found its importance somewhat less than expected. What they observed was that as model size, training data volume, and computational resources scaled up, results kept improving—leading to the catchphrase “bigger models, more data,” later formalized as Scaling Laws: every doubling of compute yields a corresponding improvement, with log-like returns.

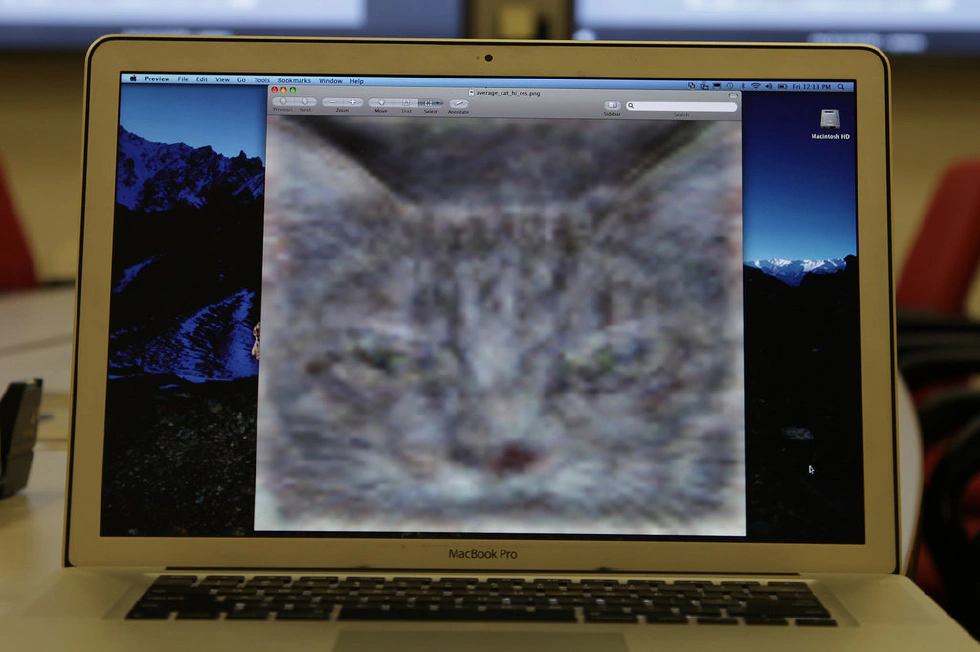

It was this insight from Scaling Laws that helped spark today’s AI boom. Jeff Dean next recalls an “aha moment” from Google Brain’s early days—a landmark widely known as the “cat discovery” in unsupervised learning, even covered by The New York Times as Google Brain’s “debut declaration.” The experiment made the model ingest 10 million random frames from YouTube videos, training it to generate higher-level features from raw pixels—essentially searching for a kind of compression algorithm able to extract key information from random images. Amazingly, the model “discovered” the concept of a cat. By analyzing which of its ~40,000 highest-layer neurons were triggered by specific images, they saw the model allocated “cat” as a feature. When they tried to “reverse-generate” images from the neurons most excited by cat pictures, an “average cat” image appeared, as did a bizarre human face.

This experiment proved neural networks could independently discover and abstract high-level concepts from vast data in unsupervised learning—without any manual pre-definition. Besides “cat discovery,” Google Brain also made breakthroughs in speech recognition and general image recognition. They used unsupervised pre-trained models that, after supervised fine-tuning on ImageNet’s 20,000 classes, cut relative error rates by 60%. In speech recognition, swapping out non-neural acoustic models for neural ones cut word error rates by 30%. And all this was achieved with only 800 machines training for five days.

Hardware Revolution: TPUs and Custom AI Chips

These stunning advances pushed Google to consider custom hardware for machine learning. Early on, some questioned whether it was needed, as huge success had already come via CPUs. However, Jeff Dean saw an urgent need for custom hardware in a 2013 experiment. He calculated that were 100 million people to speak three minutes into their phones daily, the compute required would be astronomical. They needed a better solution.

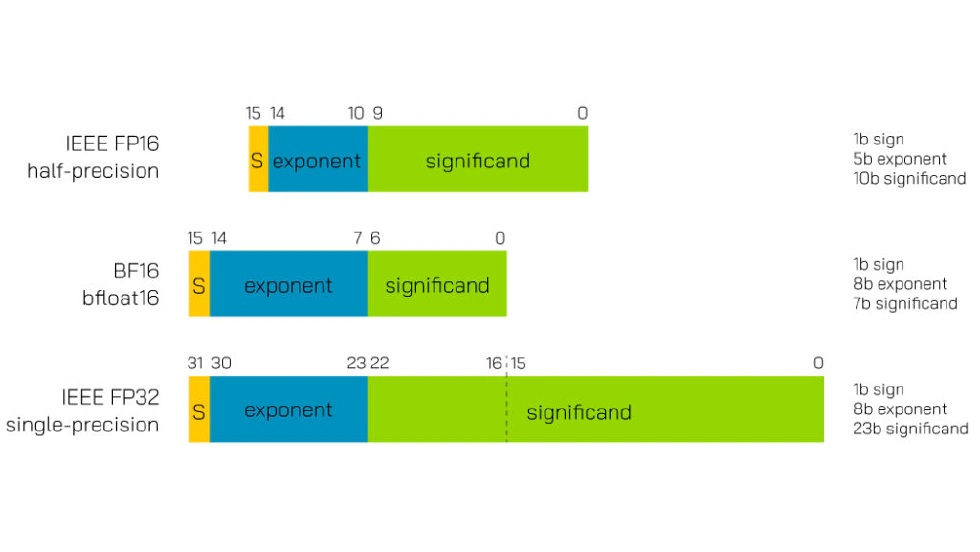

Neural networks have two key properties: first, they’re mostly driven by linear algebra operations (matrix multiplication, vector dot products); second, they tolerate lower precision extremely well. High-performance computing needs 64-bit or 32-bit floats, but neural networks can work at far lower precision. Thus, Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) were born.

The first-gen TPU focused on inference, had no floating-point ops, just 8-bit integers. Later TPUs adopted BF16, a reduced-precision float format. Jeff explains IEEE’s 16-bit float format is suboptimal for machine learning: it sacrifices both mantissa and exponent bits. In contrast, neural nets care about expressing a wide range, not tiny decimal precision. The best approach is to retain all exponent bits, sacrifice mantissa bits, and shrink from 32 to 16 bits—achieving a balance between dynamic range and sufficient accuracy.

Breakthroughs in Natural Language Processing

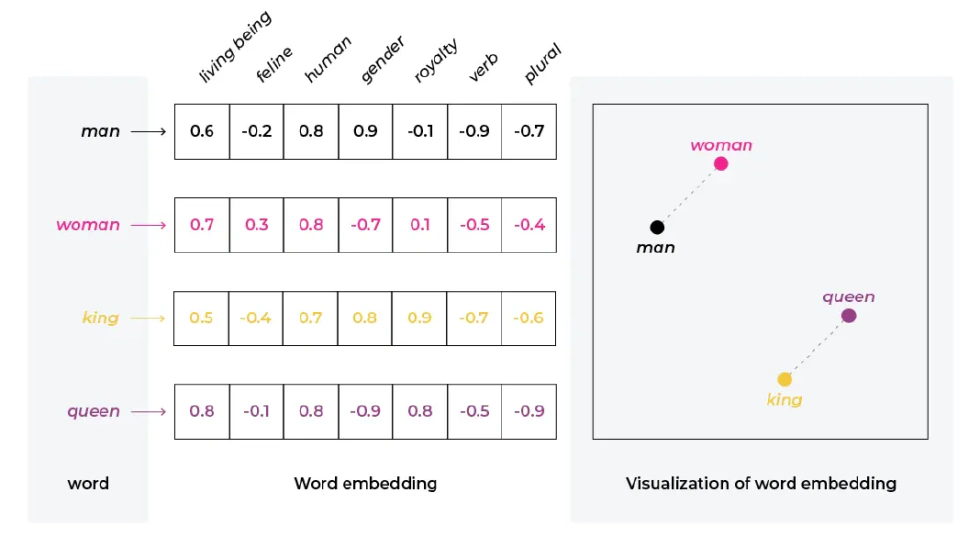

Beyond hardware, Google Brain made crucial progress in natural language processing. The most notable was perhaps the “attention mechanism.” Jeff Dean explained three main NLP breakthroughs: first, word embeddings/vector representations—representing concepts like “New York City” or “tomato” as high-dimensional vectors capturing meaning and context, enabling algebraic operations such as “king - man + woman = queen.” In high-dimensional space, vector directions are meaningful, corresponding to gender, tense, etc.

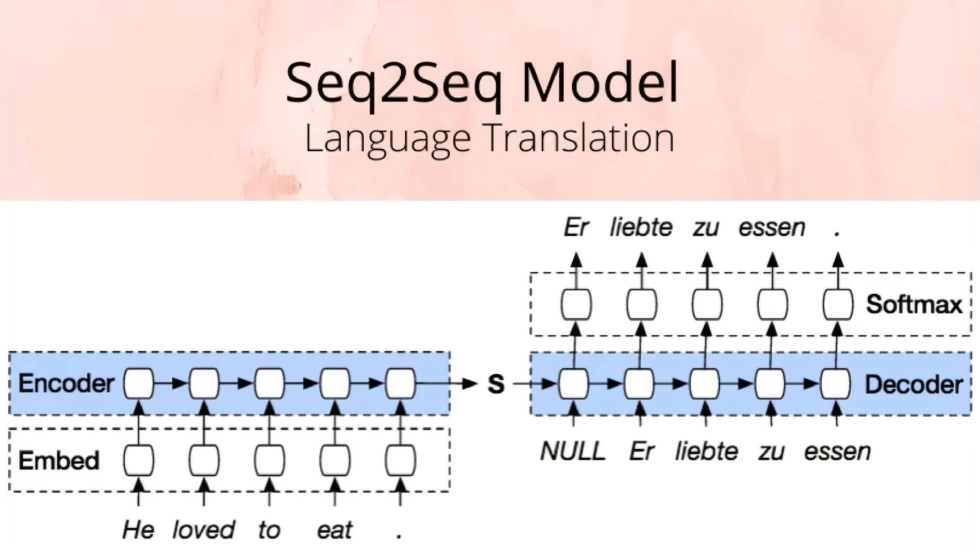

Second was the Sequence-to-Sequence (Seq2Seq) model, developed in part by Ilya Sutskever, leveraging LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) networks. LSTMs are short-term memory systems with vector states, able to process sequences of words/tokens, updating their state each time, thereby memorizing all details in vector form when scanning a sequence. The Seq2Seq model can read, say, an English sentence and use the resulting vector to initialize generation of a French sentence. These models are widely applicable, beyond machine translation, to medical records, language understanding, even genomic sequence analysis.

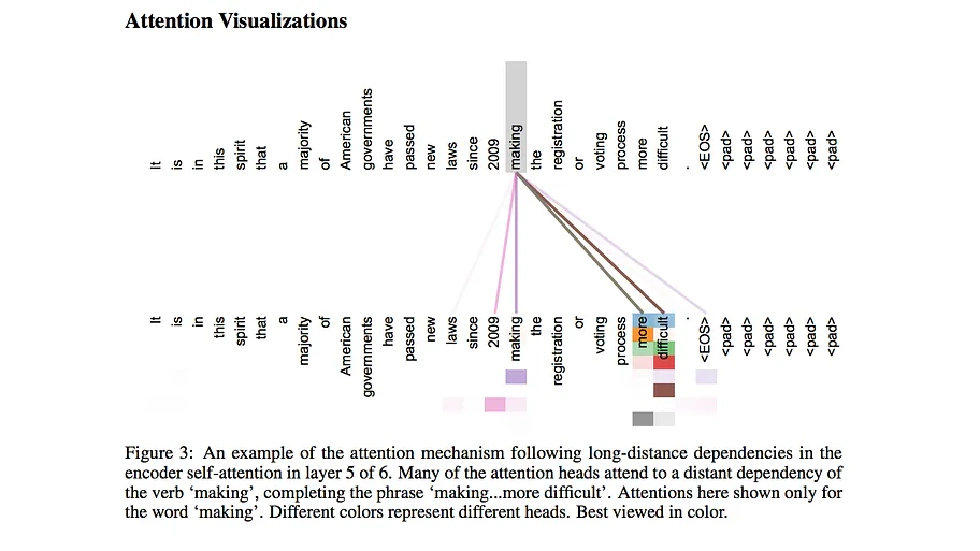

Third—and most ground-breaking—was the introduction of the attention visualizations into the Transformer architecture. Traditional sequence models updated a single state vector for every token, creating a bottleneck for information flow. Transformer attention revolutionizes this by remembering all intermediate vector states, not just one. Its complexity is O(N²), demanding more space, but it leverages matrix operations for extreme parallelism, making Transformer models vastly more efficient than predecessors.

Multimodal Models and the Future of Human-AI Interaction

Regarding the future of AI, Jeff Dean maintains an optimistic and insightful outlook. He attributes the remarkable model performance gains in the past six years to larger-scale training, higher-quality data, and powerful architectures like Transformer. More importantly, models have evolved from plain text to truly multimodal—capable of handling all human input/output forms: speech, video understanding and generation.

Such modality transformation powers new products like Google NotebookLM, where users can upload PDFs and have the model produce a podcast dialogue between two AI voices. Jeff foresees a future where humans focus less on hands-on creation and more on specifying exactly what they want. While this may not make work “easier,” it will unleash massive creativity. He likens interacting with AI models to commanding an almost omnipotent, if not always smart, genie—if you can’t articulate what you want, you can’t expect it to create anything extraordinary. Thus, prompt engineering will be key in future work and life.

Jeff also shared examples of how he uses Gemini—he likes asking Gemini to list ten supporting and ten opposing arguments for a viewpoint, finding its results exceptionally balanced and diverse, aiding his thought processes. He sees Gemini as a “Socratic partner.” Facing new fields, he asks AI questions, then deepens his inquiry based on the answers, believing that linking such world knowledge with personal preferences will be a key trend—such as recommending Arizona restaurants based on your Tokyo favorites.

Responsibility, Safety and the Social Impact of AI

Of course, Jeff Dean remains keenly aware of AI’s security, privacy, and responsibility issues. He asserts that technologists and society must continually reflect on these, as AI will profoundly impact all spheres—education, healthcare, economy. He urges everyone to actively shape the direction of AI, maximizing positive effects while guarding against negatives, such as misinformation. Jeff Dean collaborated with colleagues on a paper called “Shaping AI’s Impact on Billions of Lives,” discussing many societal issues and how to guide technology for positive outcomes and minimize harm.

Toward Fully Automated Scientific Discovery

On when AI will “break through” and surpass human creative speed, Jeff believes in some subdomains we are near or have already achieved this—and the scope will keep widening. For this, a fully automated loop is needed: idea generation, experimentation, feedback, and exploration of massive solution spaces. In domains with these features, reinforcement learning and large-scale computational search have already shown high efficiency. In areas lacking clear rewards or with slow evaluation, automation is still challenging. Yet he believes automated search and computation will accelerate progress in scientific and engineering fields—significantly boosting human capability in the next 5–20 years.

Looking Ahead

Looking ahead to the next five years, Jeff Dean hopes to focus on making powerful models more cost-effective and accessible to billions. Currently, cutting-edge models are still expensive to run; he aims to dramatically improve that. He has some new ideas in the works—though not sure they’ll succeed, exploration itself is what makes new territory exciting. Even if you fall short of your vision, the process brings invaluable discoveries.

Conclusion

As the founder of Google Brain, and key driver behind TensorFlow and TPUs, Jeff Dean has lived through the full revolution of neural networks. In the internet era, he created many legends. In today’s age of AI, let’s hope he keeps surprising us.

References

- The Moonshot Podcast Deep Dive: Jeff Dean on Google Brain’s Early Days YouTube. 2025-08-22.

- 50 Years Ago: Celebrating the Influential Intel 8080 Intel Newsroom. 2024-12-16.

- Cecil (programming language) Wikipedia.

- CSE DSI Director Honored by IEEE University of Minnesota.

- DeepSpeed Under the Hood: Revolutionising AI with Large-Scale Model Training Medium. 2024-04-09.

- Model Parallelism Medium. 2024-04-20.

- PDP-1 final checkout at DEC Mill plant Computerhistory.

- Google AI chief Jeff Dean sparks cries of hypocrisy as he urges marginalized groups to work with its researchers: ‘After what you did to Timnit?’ Business Insider. 2021-07-05.

- Spanner: Google’s Globally-Distributed Database Google Docs.

- Andrew Ng: Deep learning has created a sea change in robotics Stanford University School of Engineerong. 2019-03-05

- How Many Computers to Identify a Cat? 16,000 The New York Times. 2012-06-26

- Multiplication of Matrices - CBSE Class 12 Mathematics Chapter 3 YouTube. 2020-04-01.

- Getting Started With Embeddings Is Easier Than You Think Medium. 2022-06-03.

- Building a Seq2Seq Transformer Model for Language Translation: A Comprehensive Guide Medium. 2025-01-16.

- Attention Is All You Need arXiv. 2017-01-12

- Google upgrades NotebookLM with more sources and faster fact-checking TechFinitive. 2024-06-12

- Jeff Dean - Shaping AI’s Impact on Billions of Lives X (Twitter). 2024-12-05.