Jeff Huber: Context Engineering in AI Development

This is a topic that is both central and extremely tricky in the AI community: Have you ever felt that developing AI applications today is a bit like practicing mysterious “alchemy”? We throw all kinds of data and models into a black box, put our hands together, and hope it will produce the “gold” we want. Sometimes, it does amaze us, but more often, we’re left with a pile of inexplicable, irreproducible, and far from stable “waste.”

This is a topic that is both central and extremely tricky in the AI community: Have you ever felt that developing AI applications today is a bit like practicing mysterious “alchemy”? We throw all kinds of data and models into a black box, put our hands together, and hope it will produce the “gold” we want. Sometimes, it does amaze us, but more often, we’re left with a pile of inexplicable, irreproducible, and far from stable “waste.”

This analogy comes from Jeff Huber, founder of Chroma, a core entrepreneur in the AI infrastructure field. He believes that the current state of AI development is separated by a huge chasm between “demo” and “production.” Bridging this gap doesn’t rely on luck or repeatedly “stirring the mysterious stuff in the pot,” but requires rigorous “engineering.”

More importantly, while everyone is cheering for the million- or even ten-million-token “ultra-long context windows” promoted by large model vendors, he and his team released a report calmly telling everyone a harsh reality: “Context is rotting.” The more you stuff into the model’s head, the “dumber” it gets. Sounds counterintuitive, right?

Today, let’s review Jeff Huber’s interview on the Latent Space podcast and see how Chroma is trying to turn the “alchemy” of AI development into a true “engineering discipline.” This is not just a technical story, but also one about how to stay focused, stick to your beliefs, and pursue ultimate “craft” in the noisy AI wave.

The Origin of Chroma

To understand Chroma, we must go back to its founding. Back in 2021 and 2022, when the large model boom was just beginning, Jeff and his team had already been working in applied machine learning for many years. They repeatedly experienced a frustrating cycle: building an impressive demo was easy, but turning it into a reliable, maintainable production system was extremely difficult.

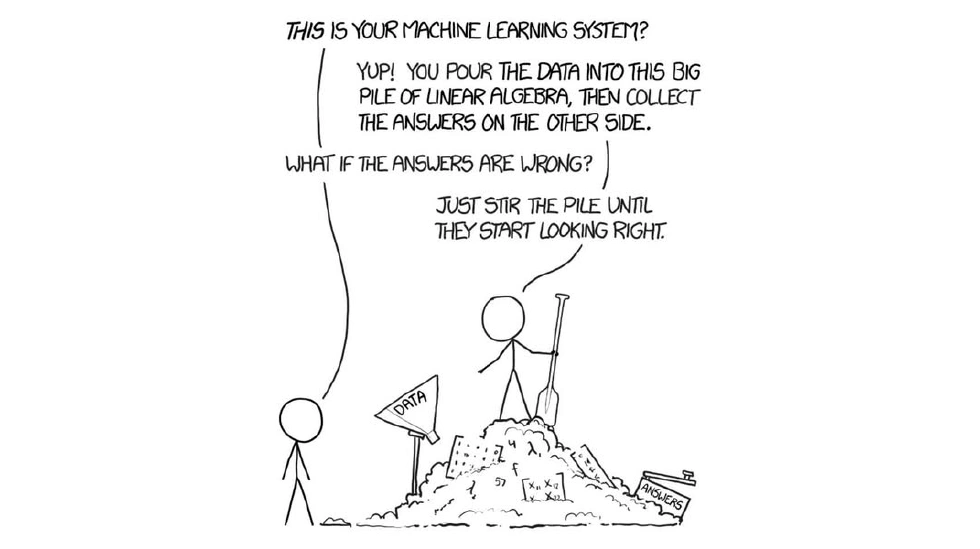

Jeff used a vivid analogy from a famous XKCD comic: A person stands atop a steaming pile of garbage. Another asks, “This is your machine learning system?” He replies, “Yup! You pour the data into this big pile of linear algebra, then collect the answers on the other side.” The other asks, “What if the answers are wrong?” He says, “Just stir the pile until they start looking right.”

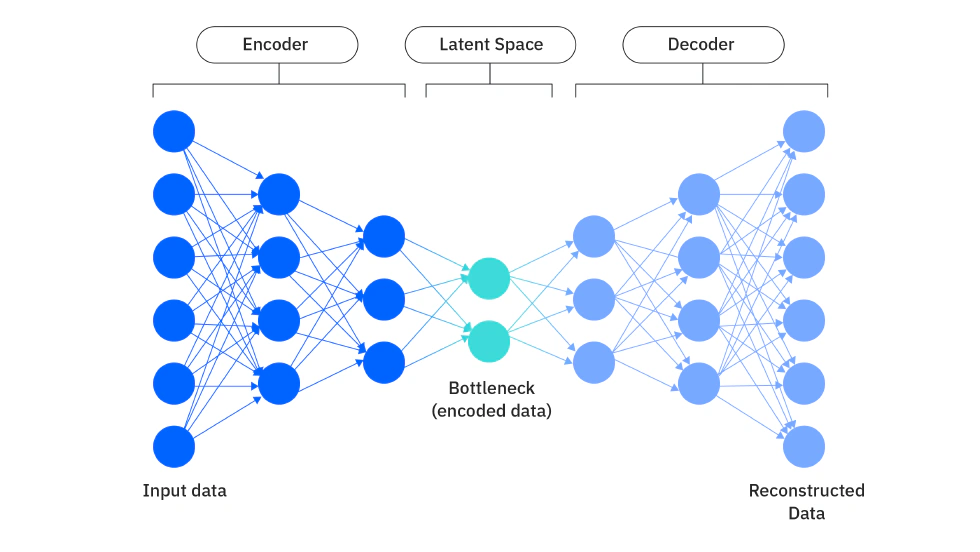

It sounds absurd, but it accurately depicts the real state of many AI application developments at the time—full of uncertainty and randomness, feeling more like mysticism or alchemy than rigorous engineering. Jeff and his team felt this was fundamentally wrong. They had a core belief: “Latent Space”—the internal way models understand and represent data—is an extremely important but severely underestimated tool.

The Mission and Focus on Retrieval

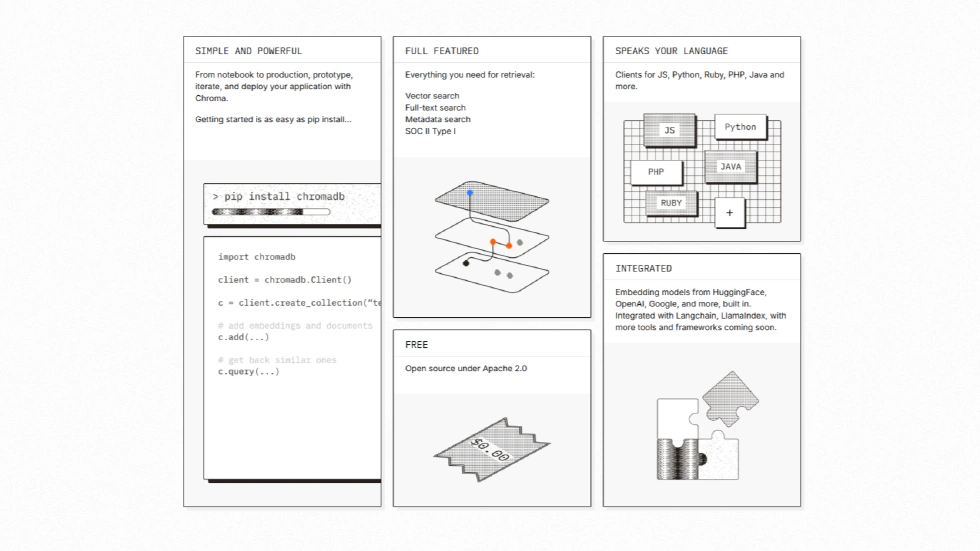

Their mission is to help developers build production-grade AI applications, turning the process from alchemy into true engineering. Early in this journey, they quickly realized that a key workload is “retrieval.” In AI applications, how to accurately and efficiently find the most relevant content from massive information to feed large models is the lifeblood of application quality.

So, Chroma decided to focus all their energy on “retrieval.” Jeff’s logic is clear: in any field, you must first reach world-class level before you’re qualified to do more. This requires an almost “paranoid” focus.

When asked what Chroma does today, the most precise answer is: they are building a modern, AI-native retrieval infrastructure. This sounds simple, but the adjectives “modern” and “AI-native” are not easy to achieve.

What Makes Chroma “Modern” and “AI-Native”

Let’s talk about “modern” first. Traditional search technologies have been around for decades. In the past ten years, distributed systems have seen new design principles and tools, such as read-write separation, compute-storage separation, high performance and memory safety from Rust, and using object storage as the core persistence layer. Chroma needed to build the entire system from scratch with these modern concepts.

“AI-native” means even deeper changes. Jeff believes this is reflected in four aspects: different technology (semantic vector search), different workloads (high concurrency and low latency), different developers (API-friendly, out-of-the-box tools), and different end users (models, not just humans, as the “user” of search).

Understanding this, we see that Chroma isn’t just adding vector search to an existing database, but rethinking and redesigning an information retrieval system for the AI era from the ground up.

The Market Environment and Chroma’s Unique Path

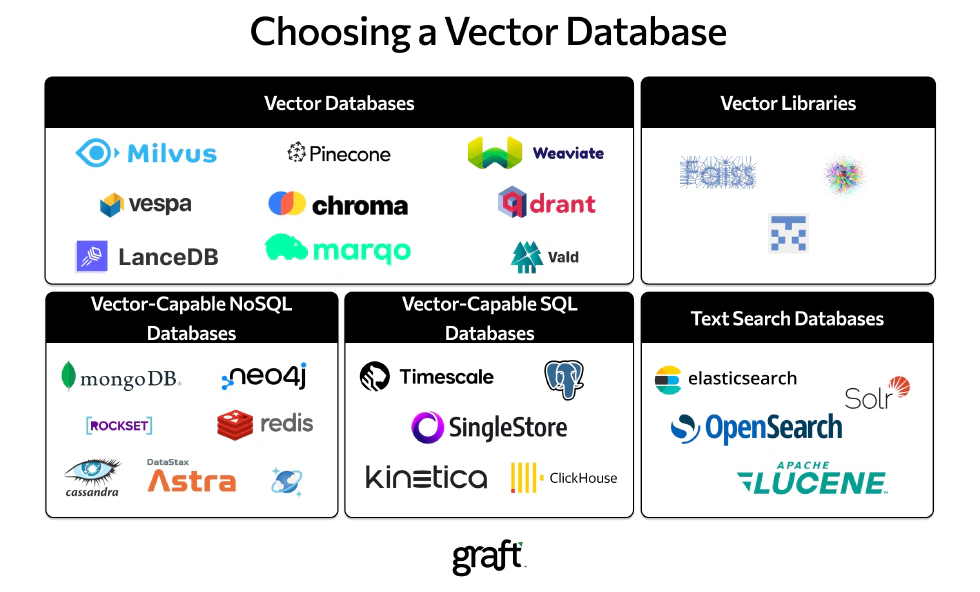

Of course, Chroma isn’t the only company with such deep thinking. Back in 2023, the vector database track was one of the hottest “trends” in AI. Companies like Pinecone raised up to $100 million, valuations soared, and new vector database products emerged one after another. In such a market, it’s hard for any entrepreneur not to feel anxious.

But Chroma’s approach was unusually “Zen” and “slow.” They didn’t rush to raise funds or launch a seemingly complete cloud product to grab the market. Instead, they spent a long time polishing the most basic open-source, single-machine product.

The Founder’s Philosophy and Developer Experience

Why? This reflects Jeff’s unique founder philosophy. He believes there are two paths to entrepreneurship: one is “lean startup,” constantly seeking market signals, like doing gradient descent, following user needs. His criticism is that if you follow this path completely, you might end up making a “dating app for middle schoolers,” because it seems to be the most basic, easily satisfied human need.

The other path is when the founder has a strong, even contrarian view—a “secret”—and obsessively pursues it. Clearly, Chroma chose the latter. For them, the most important brand asset is “developer experience.” They want the Chroma brand to be deeply associated with “ultimate craft and workmanship.”

When their single-machine product can be started in 5 seconds with just “pip install chromadb”, and runs stably on all sorts of weird operating systems—even Raspberry Pi—they could have quickly packaged it as a cloud service. But they didn’t, because Jeff believes simply hosting a single-machine software doesn’t meet their definition of “great developer experience.”

The Pursuit of the Ideal Cloud Product

Such a product would soon trap developers in the quagmire of configuring node counts, choosing machine specs, designing sharding strategies, and worrying about backup and disaster recovery—contrary to their original intention.

So, they’d rather spend more time building a truly ideal cloud product—Chroma Cloud. The design goal is for developers to feel it’s as smooth as using the local pip install version: zero configuration, no options to worry about, always fast, always cost-effective, always up-to-date, regardless of data or access volume fluctuations.

To achieve this, they had to do a lot of hard work at the bottom layer, building a truly serverless computing platform, with billing entirely usage-based—paying only for the “small slice” of compute you use, not a penny more. For many developers, especially personal projects or small apps, this could mean years of free use.

Slow Growth and the Value of Culture

This almost “foolish” persistence seemed out of place in that era of capital frenzy. While the outside world discussed “Why not use PGVector” or other alternatives, Chroma internally kept hiring at their own pace, slowly recruiting those who truly shared their vision.

Jeff has a view called “upstream of Conway’s Law”—your organizational structure determines your product form, and your company culture determines your organizational structure. So, what you ultimately “deliver” is actually your culture. That’s why he insists on slow and picky hiring, believing the future growth slope of the company depends entirely on the quality of the people in the office.

He wants to work with people he truly loves, who are willing to fight in the trenches together, and can independently deliver results that meet standards. Today, Chroma’s open-source project has over 22,000 stars on GitHub, more than 5 million downloads per month, and over 70 million total downloads. Their carefully crafted Chroma Cloud has also been officially released. All this proves that slowness and persistence ultimately build the strongest moat.

Rethinking RAG: The Rise of Context Engineering

After discussing Chroma’s philosophy and product, let’s move to the core part—their thinking on fundamental AI application issues, which I think is the most valuable part of this interview. Jeff bluntly expressed his dislike for the term RAG—“Retrieval Augmented Generation.” He said Chroma never uses this term internally.

Why? Because RAG forcibly bundles three completely different concepts—Retrieval, Augmentation, and Generation—causing great confusion. Worse, RAG has almost become synonymous with simply using dense vector search and feeding the results to the model, making the whole tech stack seem “dumb” and “cheap.”

The Definition and Importance of Context Engineering

To break this mindset, Jeff and some in the community began advocating for a more precise and “prestigious” term: “Context Engineering.” What is context engineering? Its definition is clear: the goal is to decide what information should be placed in the context window of a large language model at any generation step.

Context engineering includes an “inner loop” and an “outer loop.” The inner loop is “what should I put in this time,” and the outer loop is “how can my system learn to fill the context window more intelligently in the future.”

The Illusion of Infinite Context and the Reality of Context Rot

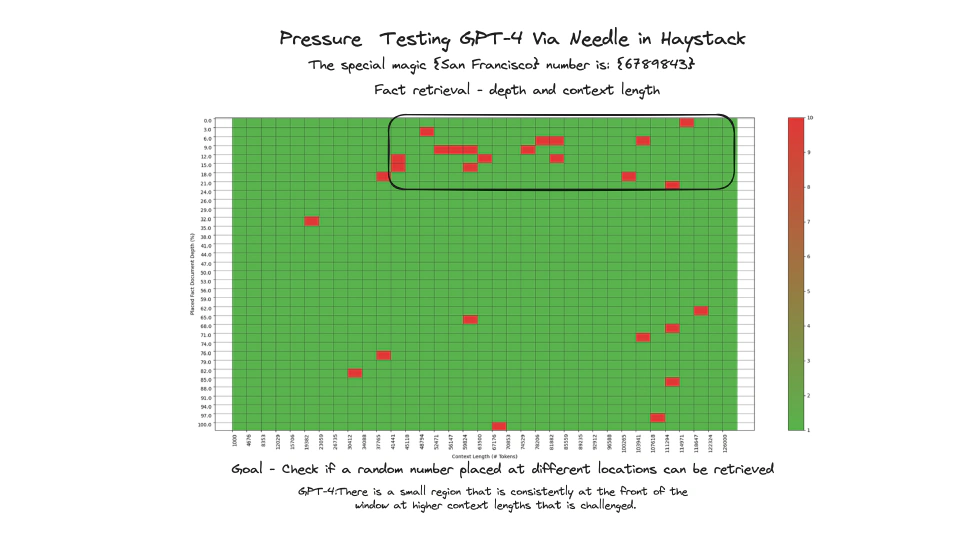

This concept is timely, as the whole industry is shrouded in blind optimism about “ultra-long context windows.” Major model vendors release perfect “Needle in a Haystack” test results, implying their models can accurately find information in million- or even ten-million-token contexts. This gives developers the illusion that we no longer need to filter information—just throw everything in.

However, reality is harsh. Chroma’s team found a widespread but rarely discussed problem: “Context Rot.” They published a technical report with experimental data showing that large language model performance is not immune to the number of tokens in the context window. As you add more tokens, the model not only starts ignoring some instructions, but its ability to reason effectively drops significantly.

Experimental Evidence and Industry Impact

This finding came from their initial research on agent learning ability. They wanted to see if letting agents remember past successes and failures would improve performance. But in experiments, as the number of conversation turns increased, the number of tokens in the context window exploded. Soon, clear instructions written in the context were ignored by the model.

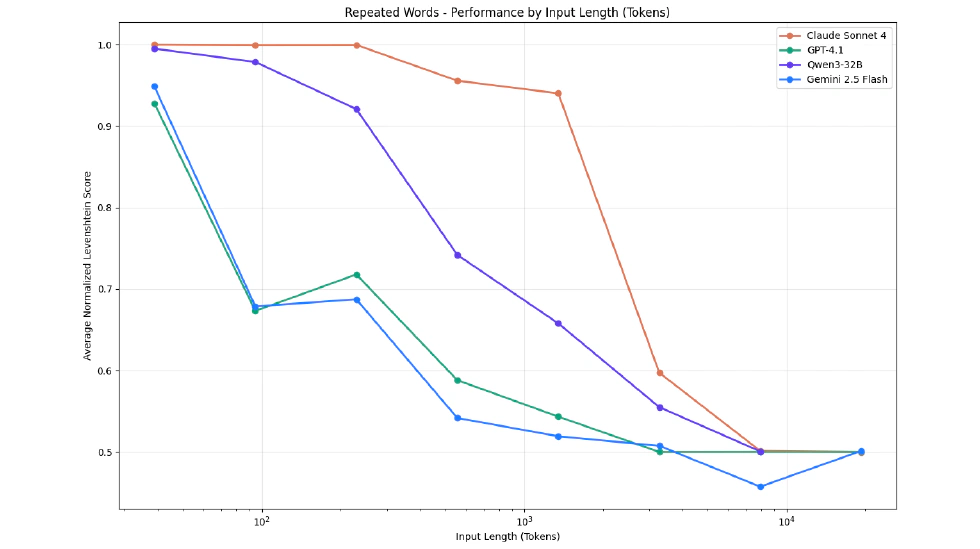

So, they decided to address this “elephant in the room.” Their report included a famous chart comparing the performance decay of mainstream models when handling long contexts. Results showed that Anthropic’s Claude 3 Sonnet performed best, while GPT-4 Turbo and Gemini Flash decayed rapidly as context length increased.

This report didn’t promote any Chroma product; it simply pointed out the problem. Jeff said he doesn’t blame these labs, as competition in large model development is fierce, and everyone naturally optimizes and promotes their strengths in benchmarks. Few will voluntarily say, “This is our product’s strength, and this is its weakness.”

The Shift from Quantity to Quality in Context

The significance of the “Context Rot” report is that it poured cold water on developers fantasizing about “infinite context.” It made clear that the length (quantity) of the context window is far less important than the quality of its content. Context engineering thus became a must-have for building high-quality AI applications, not just an optional optimization.

Jeff even asserts that the core competitiveness of any successful AI-native company today is “context engineering.”

Practical Approaches to Context Engineering

So, the question is: If context engineering is so important, what should we actually do? Currently, many developers still use the most naive method—stuffing all possibly relevant documents into the context window, which obviously triggers “context rot.” Leading teams have begun using more refined strategies. Jeff observed a mainstream pattern: “two-stage retrieval.”

Imagine you have a knowledge base with millions of document “chunks.” When a user asks a question, the first stage is “coarse filtering.” You use various signals—vector search semantic similarity, traditional full-text keyword matching, and metadata filtering—to quickly select a few hundred highly relevant candidates from millions. This stage prioritizes “recall”—better to include too many than miss one.

Then comes the second stage: “refinement.” Here, people increasingly use a powerful tool—the large model itself—for “re-ranking.” You can feed these hundreds of candidate chunks, along with the original question, to a large language model and let it judge which chunks are “most” relevant, scoring and ranking them. In the end, you might only select the top 20 or 30 chunks to put into the final model’s context window.

The Feasibility and Future of Two-Stage Retrieval

You might think calling the large model hundreds of times sounds expensive and slow, but as inference costs plummet, this “brute force” approach is becoming more feasible. Jeff even boldly predicts that as large models get faster and cheaper, dedicated re-ranking models may disappear in most scenarios, just as we rarely design custom ASIC chips for specific tasks today—everyone will use general-purpose large models for this.

This paradigm also applies in more specialized fields like code retrieval. Code is highly structured and logical, so retrieval can’t rely solely on fuzzy semantics. Thus, in addition to vector search, precise tools like regex remain crucial. Chroma natively supports fast regex search in their system.

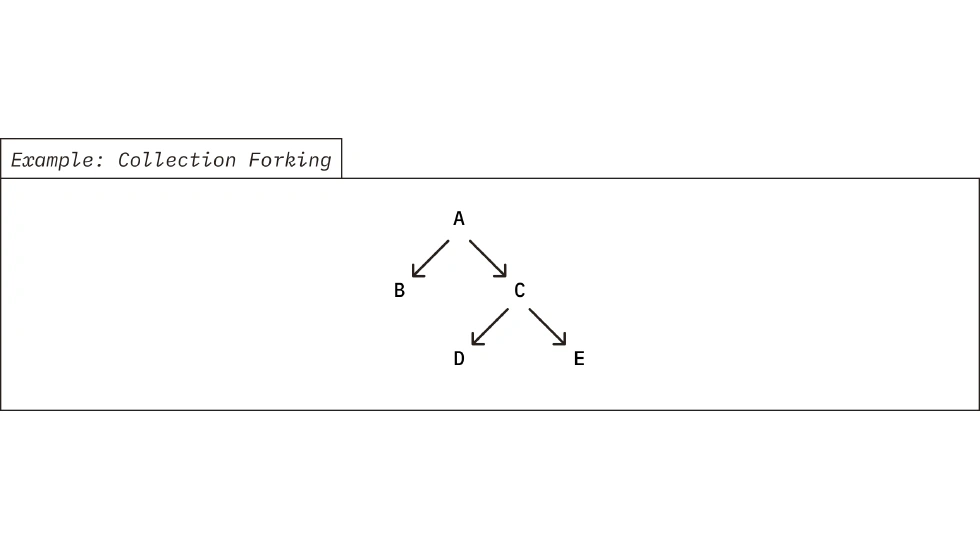

They also developed an interesting feature called “index forking.” Developers can create a nearly zero-cost copy of an existing index in milliseconds. This means you can create a separate, searchable index for every commit or branch in a code repository—an invaluable tool for tracking code history or comparing versions.

Memory as a Product of Context Engineering

At the end of the interview, Jeff shared his views on AI system “memory.” We often hear about complex theories of long-term, short-term, and working memory, but Jeff thinks these are unnecessary complications. He believes “memory” is simply the fruit of the “context engineering” tree. In other words, if memory is a benefit, context engineering is the tool to achieve it.

A good memory system is essentially a good context engineering system: it knows how to store information when the user says “remember this,” and how to retrieve it precisely in later interactions.

Generative Benchmarking and Data Labeling

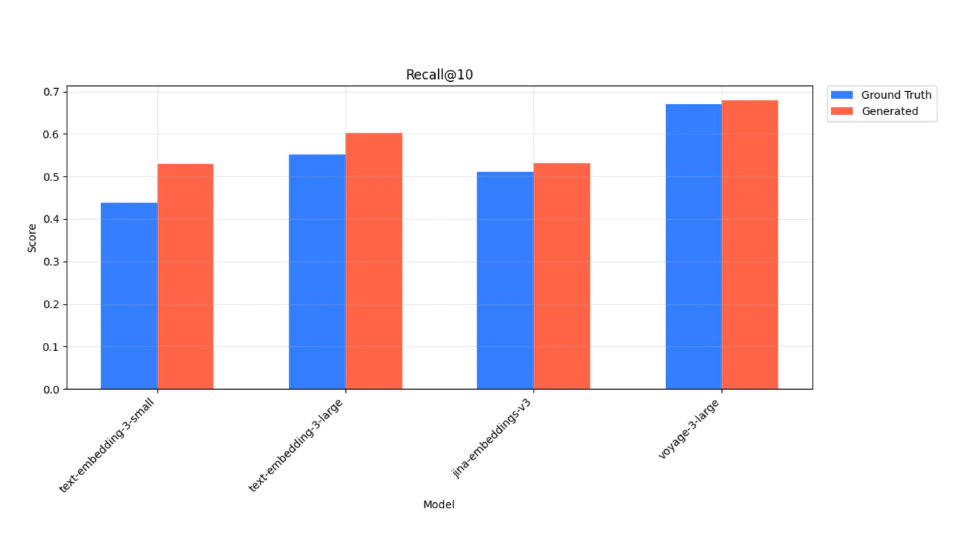

How to make this system better? Chroma proposed a practical methodology and released another technical report: “Generative Benchmarking.” To evaluate a system, you need a “golden dataset”—a set of standard questions and answers. But for your private knowledge base, who writes the questions and answers? It’s a time-consuming process.

Chroma’s method is to let large models help: have the model read your documents and generate possible user questions, quickly creating a large set of question-answer pairs to form your golden dataset. With this, you can quantitatively evaluate your retrieval system: for example, after changing an embedding model, did your retrieval accuracy improve from 80% to 90%? How much did adding a re-ranking step help? All optimizations become evidence-based, not just “stirring” by feel.

Jeff also encourages all teams to spend an afternoon, order some pizzas, and hold a “data labeling party” to manually create even a few hundred high-quality labeled data points. This small investment yields huge returns in system performance.

From Alchemy to Engineering: Chroma’s Broader Impact

This is the thinking Chroma brings us: turning AI development from an “alchemy” dependent on intuition and luck into an “engineering” process that is measurable, iterative, and optimizable.

At this point, you may realize that Chroma’s success is not just technical, but also a cultural victory. Jeff, reflecting on his previous entrepreneurial experiences, admitted he often compromised—working with people he didn’t quite fit with, or serving customers he didn’t love. But now, as he’s grown older, he’s realized that life is short and you should only spend time on work you truly love, with people you truly appreciate, creating value for users you truly want to serve. This may sound idealistic, but it’s this belief that shapes Chroma’s character.

He notes that today’s society, especially the tech world, is filled with nihilism. But in his view, people need faith, need to start grand projects whose results they may never see in their lifetime—like building a cathedral that takes centuries to complete. This belief ultimately shows in every detail of the company. Jeff strongly agrees with the saying, “How you do anything is how you do everything.” So, you’ll see Chroma’s office design, website, documentation, even T-shirts, all exude a highly unified, thoughtful sense of “design” and “quality.” This pursuit of “craft” is consistent with their product philosophy. In his view, the founder is the company’s “curator of taste.” When this insistence on quality is passed from the founder to every employee, it becomes the company’s culture and is reflected in the product and brand you see.

Conclusion

That’s the story of Chroma for today. From “alchemy” to “engineering,” from “context rot” to “context engineering,” from the myth of “infinite context” to the practice of “golden datasets,” Chroma brings us not just a useful tool, but a way of thinking and philosophy for serious, rigorous system building in the AI era. I hope today’s sharing can inspire you as you explore the AI field.