Rich Sutton: OaK—Superintelligence from Experience

When the giants of the AI industry are still chasing scaling laws, a leading academic figure has issued a warning: to some extent, the AI industry has already lost its way. The person who said this is none other than Rich Sutton, the father of reinforcement learning and a Turing Award winner.

When the giants of the AI industry are still chasing scaling laws, a leading academic figure has issued a warning: to some extent, the AI industry has already lost its way. The person who said this is none other than Rich Sutton, the father of reinforcement learning and a Turing Award winner.

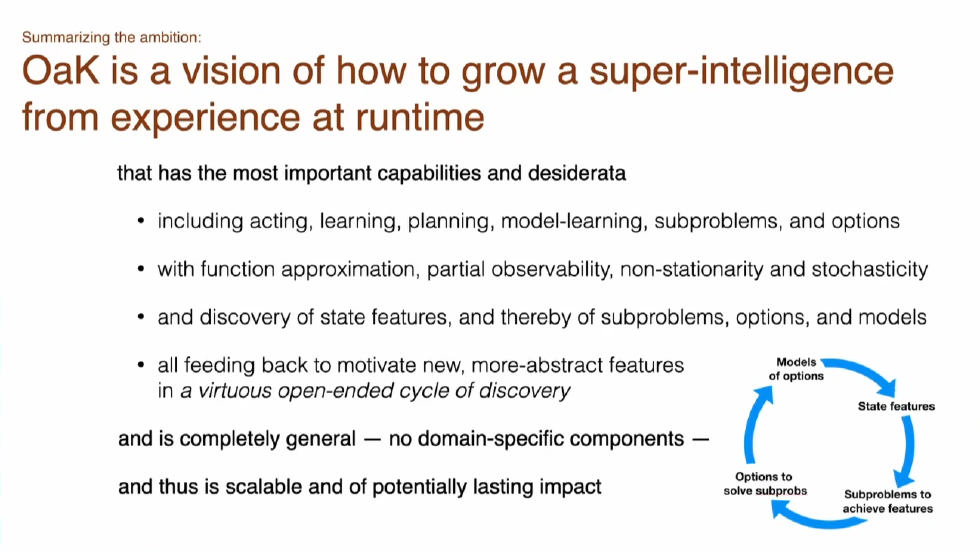

At RLC 2025, Sutton once again presented a grand vision, directly addressing the ultimate question of AI: How will superintelligence emerge from experience? He named this architecture “Oak”—Options and Knowledge Architecture. This is not just the release of a technical framework, but more like a manifesto.

It deeply criticizes the current AI field’s path dependence on large language models and tries to refocus research on the most classic and core proposition: How can we create an agent that, like us, learns and grows continuously through interaction with the world over its lifetime? Sutton believes that to get back on the right track toward “true intelligence,” we need to do several things:

- Build agents capable of continual learning

- Enable agents to construct world models and plan

- Allow agents to learn high-level, learnable knowledge

- Achieve meta-learning generalization

The OaK architecture is his response to all these needs. Today, let’s learn about the different new path Sutton has outlined for us.

Redefining the Ultimate Goal of AI

In his talk, Sutton redefined the ultimate goal of AI research, describing it as a great expedition, as important as the origin of life on Earth. Because we are not just building a powerful tool, but also trying to understand the nature of mind. He said, strangely enough, the biggest bottleneck is our lack of sufficient learning algorithms. Our current algorithms, including deep learning, are still very crude.

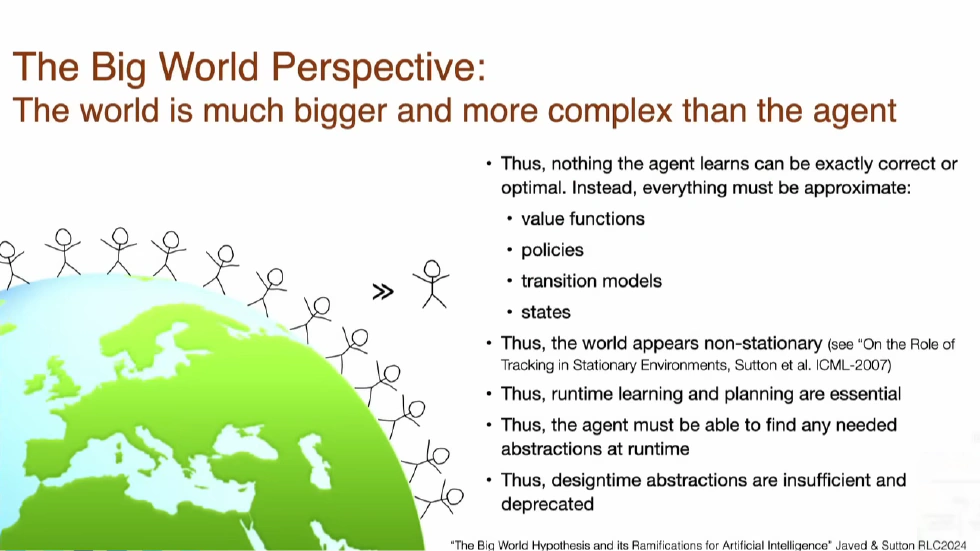

In the following talk, Sutton established a grand worldview, which is the cornerstone of all his thinking. He calls it the “Big World Perspective.” The core of this perspective is a simple yet profound idea: the world is far larger and more complex than the agent itself. The world contains billions of other agents, all the complex details of atoms and objects. What happens in the minds of your friends, lovers, or even enemies is closely related to you.

In this “big world,” an agent can never obtain complete and precise knowledge about the world. Therefore, its value function must be approximate, its policy suboptimal, and its world model highly simplified. More importantly, because the agent cannot observe the entire state of the world, the world must also appear non-stationary to it. This seemingly simple assumption directly leads to Sutton’s first core criticism of the current AI development path.

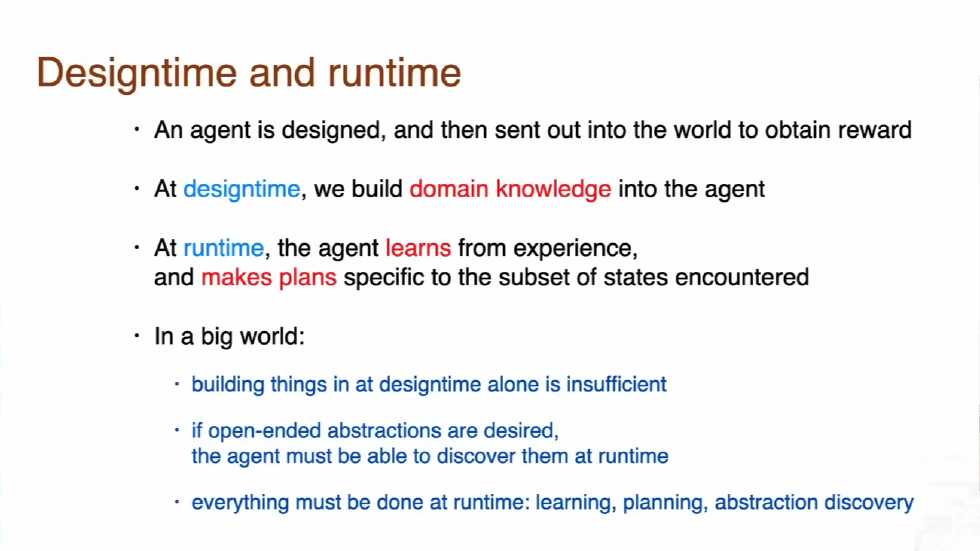

Design Time vs. Run Time

Design time refers to the stage where human engineers build knowledge and capabilities into the agent before deployment, in the factory or before the model is released. Run time refers to the stage after the agent is deployed in the real world, where it learns and grows through real-time interaction with the environment. Sutton bluntly points out: for a large language model, everything is done at design time. When it is deployed in the world, it does nothing more—it no longer learns.

His view is very clear: all important things must be accomplished at run time.

Why? Because in a big world, you cannot foresee all the situations the agent will face at design time. For example, a home robot needs to remember its owner’s name, the content of work projects, who its colleagues are—these cannot be pre-built into its domain knowledge. It must learn and adapt at run time.

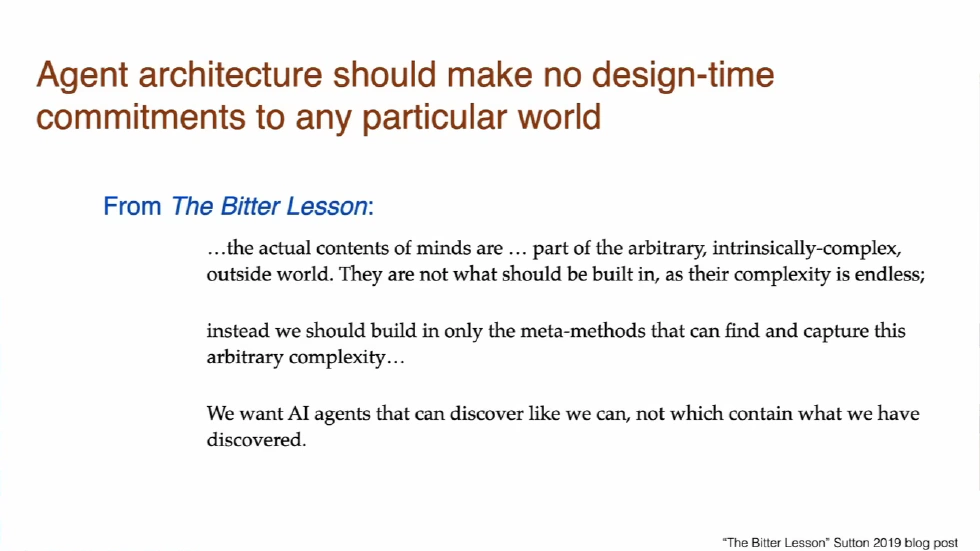

This naturally leads to Sutton’s famous assertion from years ago, “The Bitter Lesson”: what we want to build are agents that can discover as we do, not agents that contain only what we have already discovered. Large language models, in a sense, are the ultimate embodiment of containing what we have already discovered. They build a huge knowledge base by ingesting massive amounts of human knowledge at design time, but lack the ability to discover new knowledge and abstract new concepts at run time.

Sutton believes this is putting the cart before the horse. The core capability of true intelligence should be learning at run time, and what is provided at design time should only be the most general meta-methods that support such learning.

However, he also points out the huge technical bottlenecks currently facing run-time learning, including catastrophic forgetting and loss of plasticity. This is why today’s deep learning methods do not perform well in continual learning.

This is the era-defining question Sutton raised in his talk: while the entire industry cheers for scaling laws and pushes the parameter race of large models to new heights, have we overlooked the more fundamental things necessary for true intelligence?

The OaK architecture is his answer.

The Three Core Principles of OaK

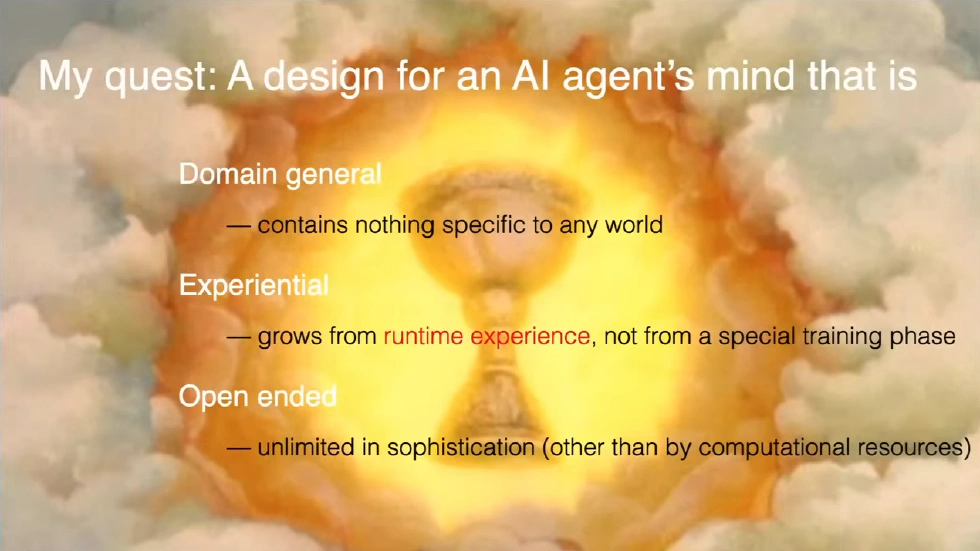

Before constructing the OaK architecture, Sutton first clearly defined the three core design goals—the “Holy Grail” of AI he pursues. These three principles support the entire philosophy of the OaK architecture:

Domain General

The design of the agent itself should not contain any knowledge about a specific world. This is a very radical but extremely pure goal. Sutton emphasizes that this does not deny the value of domain knowledge in specific applications. If you want to quickly develop an application to solve a specific problem, embedding some domain knowledge is certainly efficient. But if your goal is to understand the nature of mind, to find a simple and universal theory of how intelligence works, then you must exclude arbitrary, inherently complex details of the external world from the core design of the agent. The agent’s task is to learn the quirky, intricate details and high-level structures of the world, not to make these details part of its own design. We want a simple, elegant principle of intelligence that can understand any world, not a complex encyclopedia filled with knowledge of specific worlds. In short, knowledge about specific worlds should be learned by the AI itself, not hard-coded by human engineers.

Experiential

The mind of the agent should grow entirely from run-time experience, not rely on a special training phase. This principle is consistent with the discussion of design time and run time. Sutton’s logic is very clear: since in a big world, the agent must be able to learn, plan, construct, and adjust abstract concepts at run time, why not make this ability the sole core of the design? Abilities pre-built at design time may give the agent a head start, but from the perspective of conceptual simplicity, a design that relies solely on run-time experience is undoubtedly more fundamental and elegant. In other words, since you must be able to do these things at run time, why not just do them all in one place?

Open-Ended

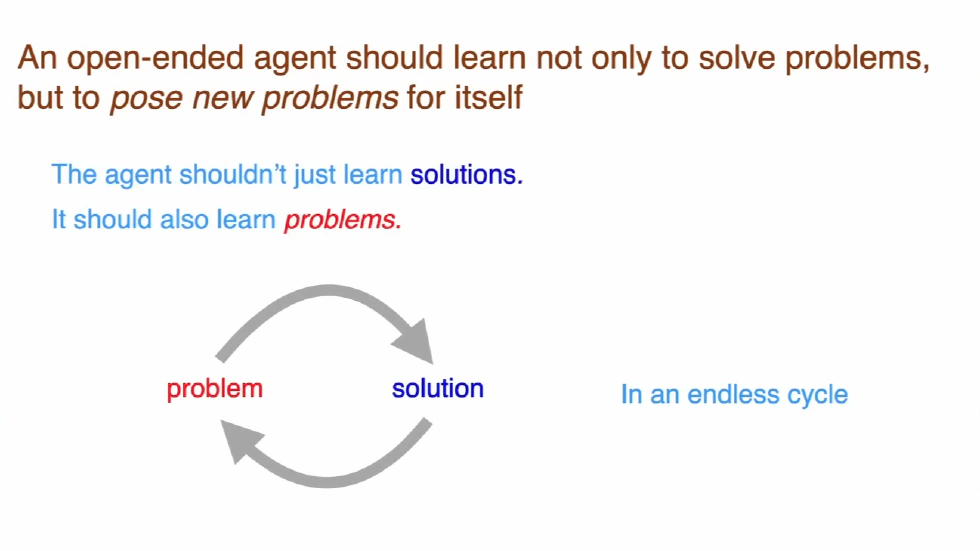

The agent should be able to continuously create any concepts and abstractions it needs. The upper limit of this complexity should only be restricted by its computational resources. This is the key to superintelligence. The agent cannot stop at learning preset features or concepts; it must be able to discover connections in the world through interaction, define new and more useful concepts, and use these new concepts to build more complex knowledge systems. At the same time, this process must be open-ended and never-ending.

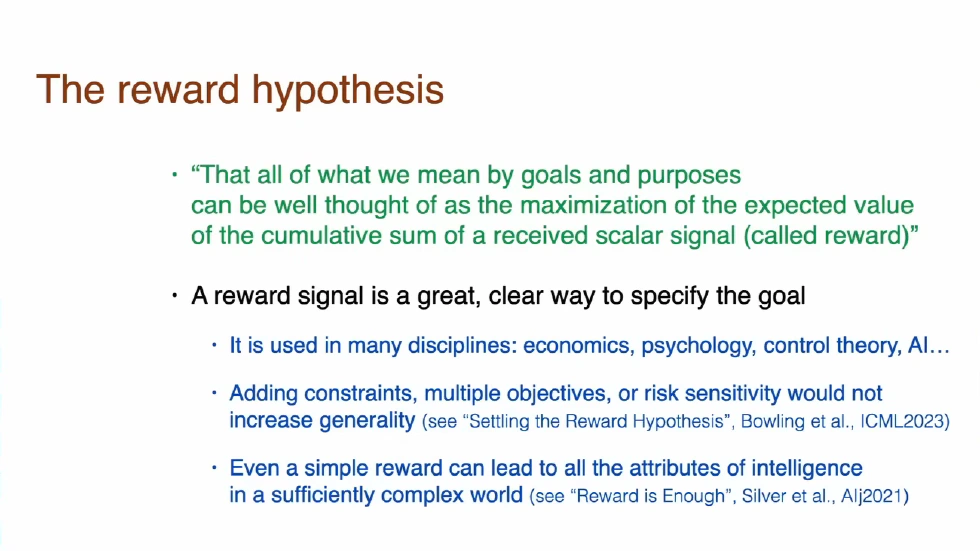

The Reward Hypothesis

To provide a clear objective function for these three principles, Sutton reiterates his firmly held “reward hypothesis”: all goals and purposes can be well understood as maximizing the expected cumulative sum of a received scalar signal—reward. This hypothesis unifies all complex behavioral motivations of the agent into an extremely simple mathematical framework. Whether it’s seeking food, exploring the unknown, or creating art, the fundamental driving force of these behaviors can be modeled as maximizing a single scalar reward signal. In a sufficiently complex world, simply maximizing a simple reward signal is enough to give rise to all the attributes of intelligence as we understand it.

At this point, Sutton’s vision of the AI Holy Grail is becoming clear: a domain-general agent, learning entirely from run-time experience, in an open-ended process of abstraction creation, with maximizing scalar reward as its sole objective, ultimately growing into true superintelligence.

With a clear goal, we can unveil the mystery of the OaK architecture.

The Core of OaK: Options and Knowledge

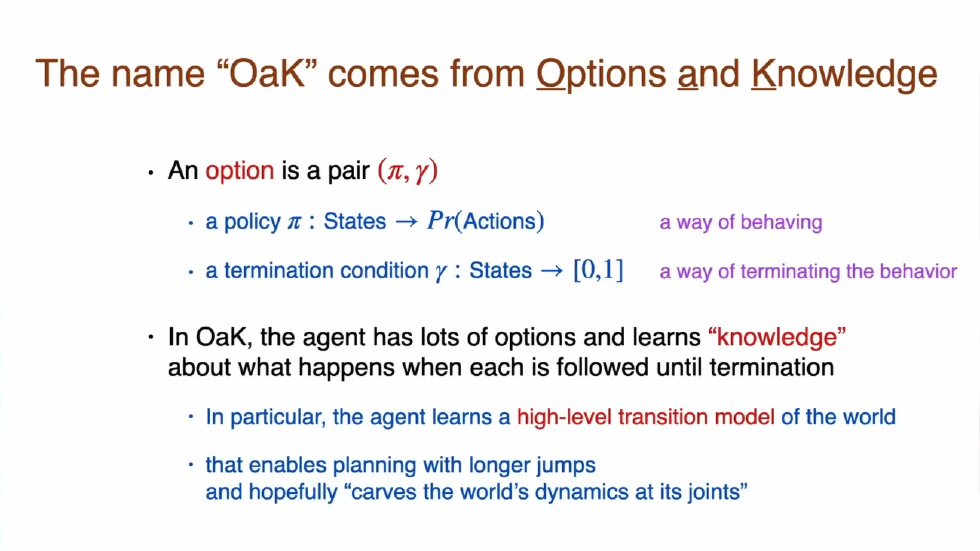

First, let’s break down its name: OaK—Options + Knowledge.

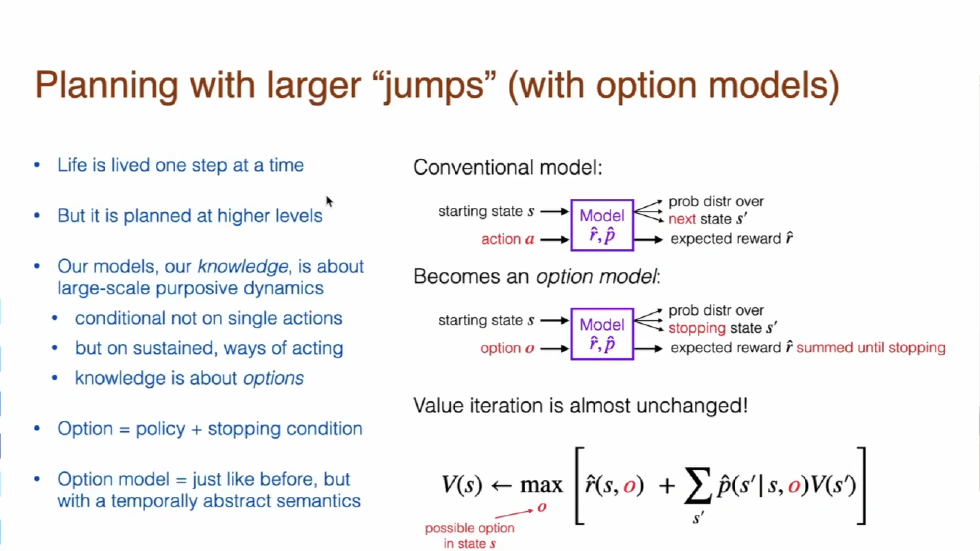

Let’s start with Options. In reinforcement learning, an Option is a temporally extended action. It’s not just an atomic action, like taking a step to the left, but a behavioral chunk that includes its own policy and termination condition, such as the option “walk to the door.” Knowledge, in the OaK architecture, specifically refers to the model of what happens when you execute a certain Option. This is a higher-level world model, allowing you to reason and plan at larger time steps.

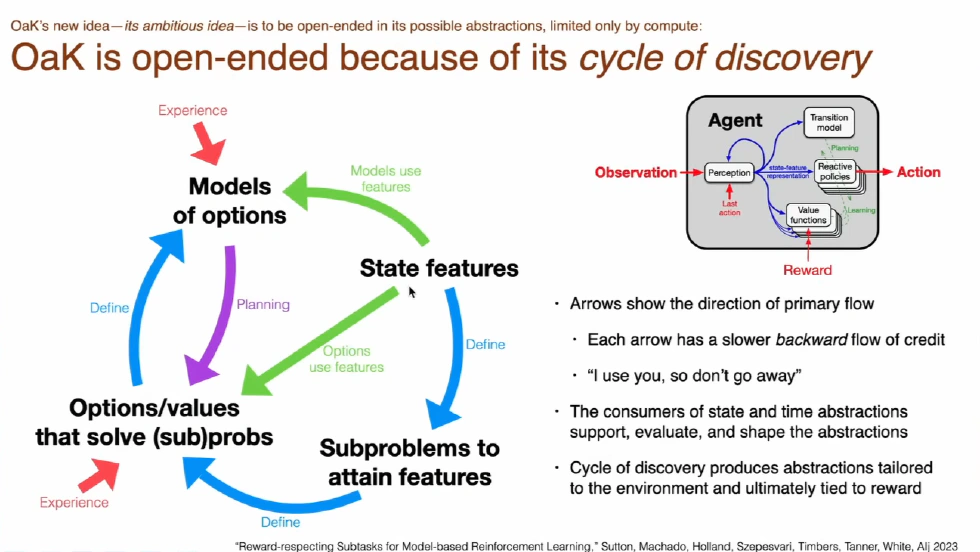

Therefore, the core of OaK is to let the agent continuously learn new Options and build Knowledge about the world around these Options, enabling the agent to understand and plan the world at a higher, more abstract level, thus making jumps on larger time scales and dissecting the world at key nodes.

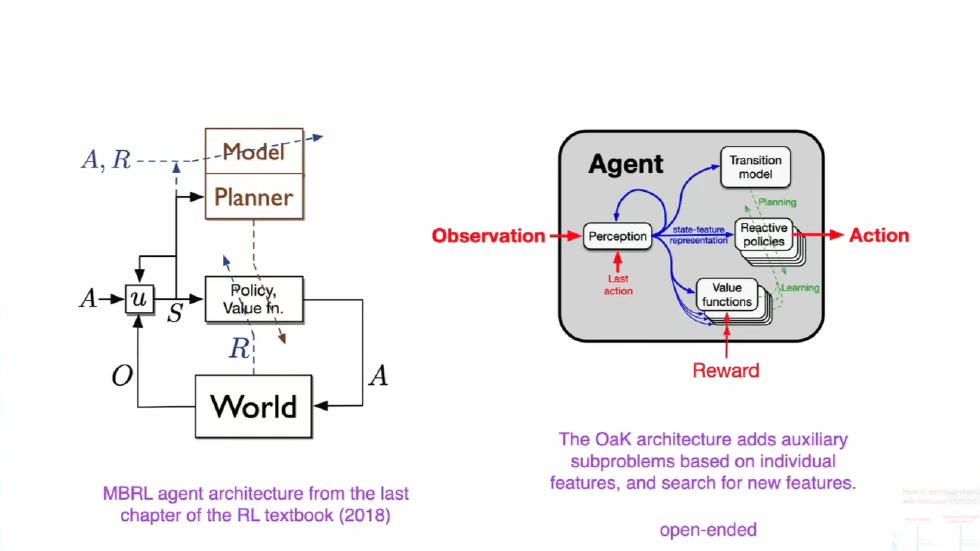

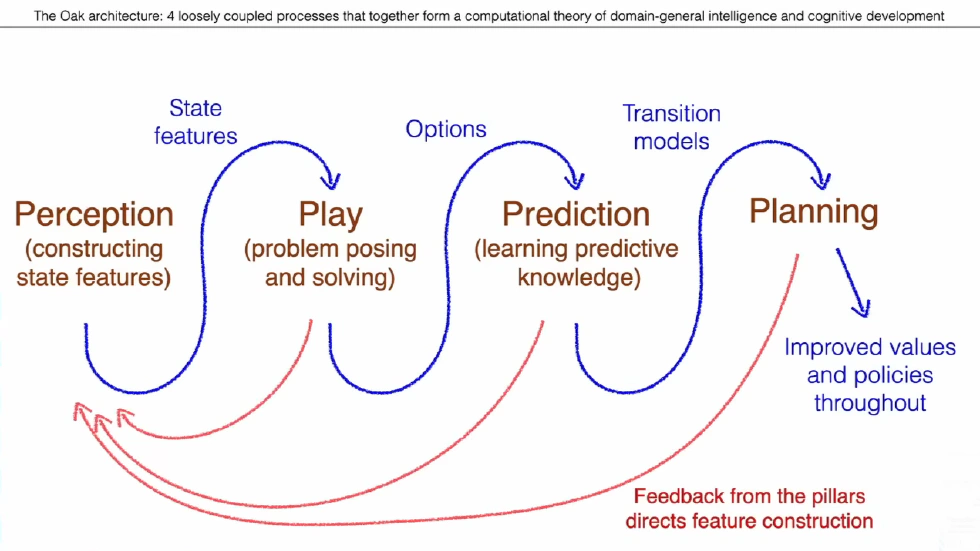

From the overall schematic of the OaK architecture, we can see that it contains all the components of a classic reinforcement learning agent: receiving observations and rewards from the world, outputting actions, and internally having a policy, value function, world model, and planner. But the most crucial difference is the Auxiliary Subproblems.

The Role of Auxiliary Subproblems

Sutton believes that an agent should not have only one main task given by the environment, such as maximizing the reward signal. It must be able to create new, internally driven subproblems for itself. This is also a problem that has puzzled AI and cognitive science for many years: what is the essence of curiosity, intrinsic motivation, and play?

Sutton explains this with a vivid example: a young chimpanzee swings on a branch, not to get food, but simply because it is interested in the feeling of swinging. A baby shakes a rattle repeatedly, not to accomplish an external task, but to reproduce and understand the interesting sound. These so-called playful behaviors, in Sutton’s view, are the agent setting subproblems for itself.

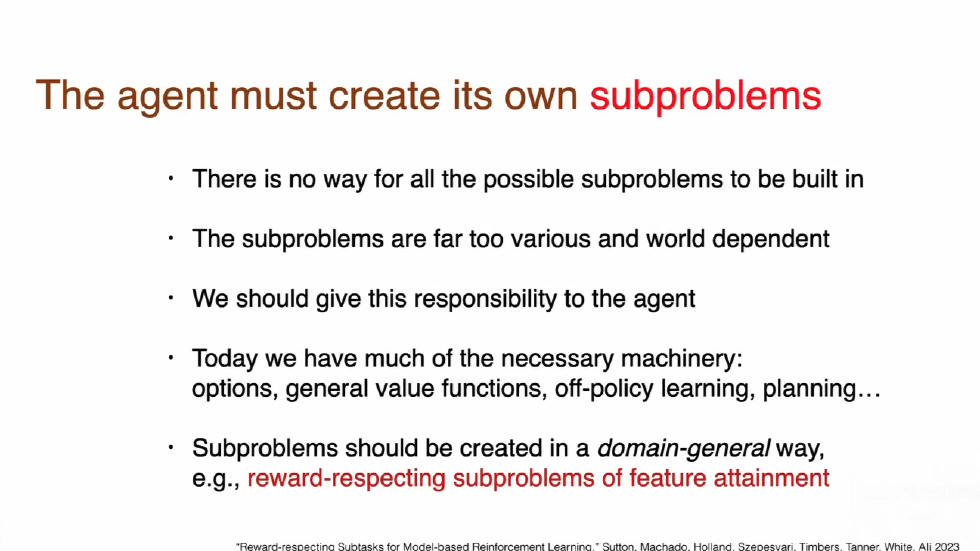

So where do these subproblems come from? Sutton gives an extremely simple mechanism: they come from features. When the agent interacts with the world, its perceptual system constructs state features of the world. These features can be anything—a bright spot, a particular sound, or a special feeling.

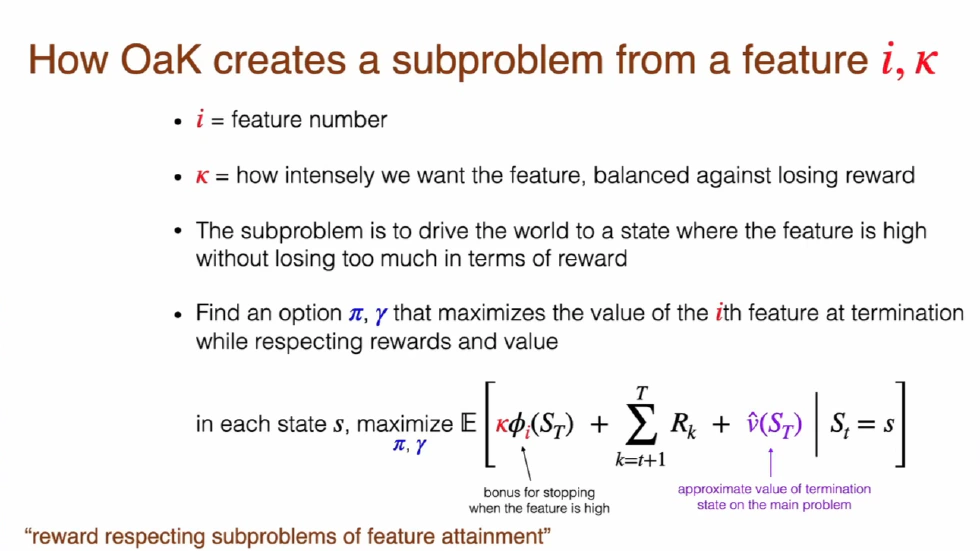

Therefore, the core idea of the OaK architecture is that any sufficiently interesting feature can become the goal of a new subproblem, defined as “feature attainment respecting reward.” Specifically, for a certain feature i, the agent creates a subproblem whose goal is to maximize the value of feature i as much as possible, without losing too much main task reward. The brilliance of this definition is that when the agent pursues its small goals, such as exploring an interesting sound, it does not completely forget its big goal, such as survival—it balances the two. For example, to get a cup of coffee (achieve the “coffee” feature), it will look for a safe path rather than jump off a cliff, which would result in a huge negative reward.

In this way, the agent can continuously create intrinsic motivation to explore the world, building a perpetual learning loop of continual discovery and abstraction. Sutton describes it as a run-time loop composed of multiple parallel steps—the growth pattern of the tree of wisdom in the OaK architecture.

The Learning Loop in OaK

Everything starts with perception. The agent needs to construct a description of its current state from the raw data stream of interaction with the world, such as observations and actions—these are state features. Sutton emphasizes that this process is not to approximate some human-labeled tag or the true state of the external world, but to serve the agent’s own decision-making and learning. Whether a feature is useful depends on whether it helps the agent solve problems better.

The agent has an internal evaluation mechanism. When it constructs or discovers an interesting feature, it turns that feature into a new goal—a subtask. Then, based on these high-value features and the principle of “feature attainment respecting reward,” it generates a series of new subproblems. Sutton believes the agent must be able to create its own subtasks, not wait for humans to set them.

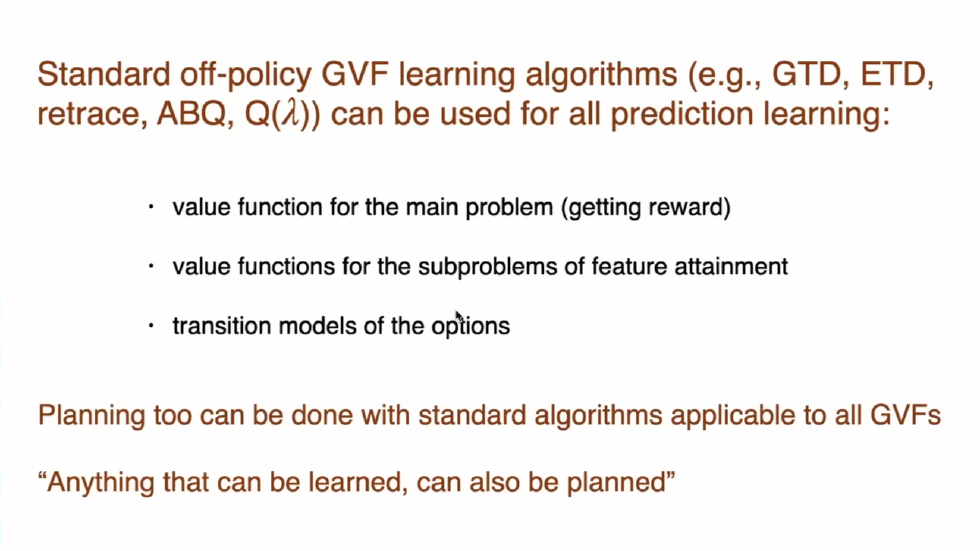

Once a subtask is proposed, the agent uses reinforcement learning to learn a policy that can accomplish this subtask—an Option. For example, for the subtask of making the rattle sound again, the agent may learn an Option that includes a series of specific arm and wrist movements, and terminates when the sound is heard. Thus, the OaK architecture contains many such Options, each corresponding to a subtask derived from a feature.

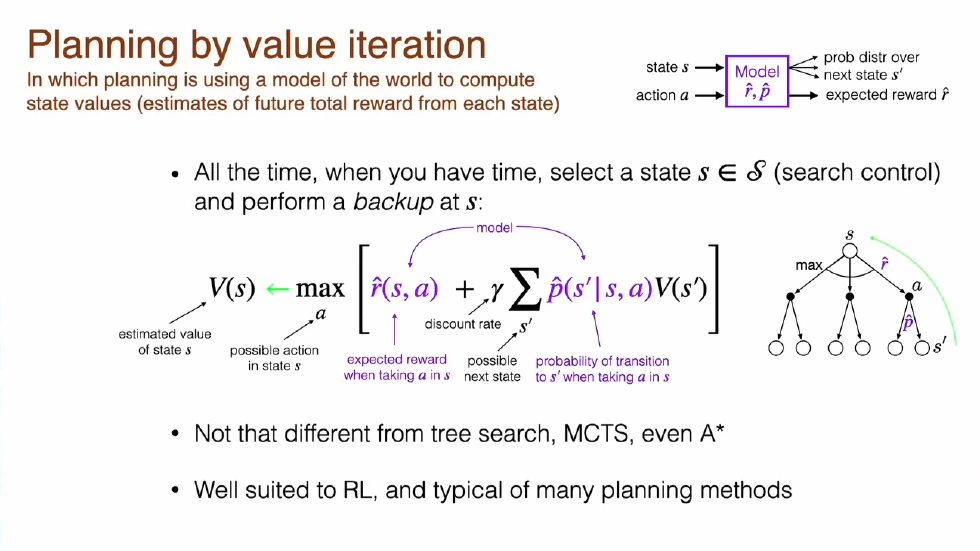

After the agent has many Options, the next step is to learn a model for each Option. This model answers: if I initiate the “make rattle sound” Option in a certain state, what changes will happen in the world? What new state will I reach? How much reward will I get in the process? This is a high-level, temporally abstract world model—not modeling single-step atomic actions, but predicting the outcome of entire behavioral chunks (Options). This gives the agent a qualitative leap in planning ability.

With a high-level world model based on Options, the agent can plan efficiently and for the long term. It can mentally simulate the consequences of executing a series of Options, like playing chess in its mind, to find the best macro-strategy for the main task, and update its overall policy and value function accordingly. When facing a new goal, such as a change in the main task reward, it no longer needs to simulate step by step from atomic actions, but can think directly at the level of Options: e.g., “I can first execute the ‘walk to the door’ Option, then the ‘open the door’ Option,” and so on. This kind of high-level, abstract planning is far more efficient and profound than single-step planning.

Sutton emphasizes that the essence of planning is to use the model to keep the value function dynamically aligned with the world. Note that these steps are not executed linearly just once—they form a perpetual learning loop. The key to the loop is feedback. When the agent uses learned Options and Models for planning, it finds that some Options are particularly useful for solving the main task, some Option models are easier to learn and predict more accurately, or that some low-level state features are more useful than others when learning an Option’s policy or model. This information forms a feedback signal that tells the feature construction module in step one which types of features are useful and which are not. This feedback mechanism guides the agent to construct more and better new features, which in turn become the raw material for proposing new subtasks, starting a new round of Option learning, Model learning, and Planning.

In this way, as the agent solves simple subtasks, it discovers the features needed to construct more complex subtasks, and from solving these complex subtasks, it discovers features for even more complex tasks. This cycle repeats endlessly, causing the agent’s cognitive ability and level of abstraction to snowball and self-improve, ultimately forming an open-ended, unlimited ladder of intelligent growth.

The Mechanistic Answer to Superintelligence

This is Sutton’s mechanistic answer to how superintelligence emerges from experience. It tells us that intelligence is essentially an eternal cycle of self-driven, self-creating, and self-improving processes.

The Challenges Facing OaK

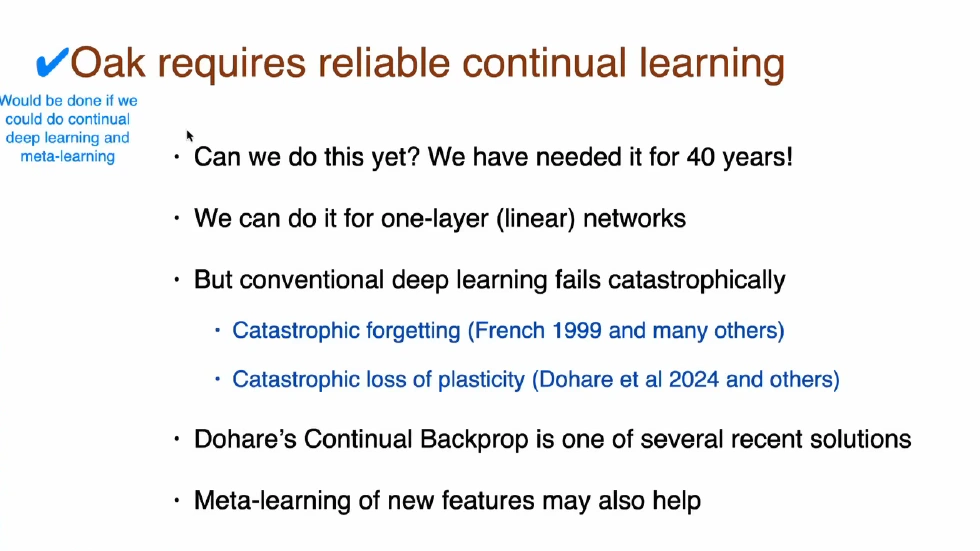

Although the vision of the OaK architecture is exciting, Sutton also candidly pointed out the huge challenges and some key missing technical pieces in realizing this grand vision. The two most critical and difficult problems are exactly what we mentioned at the beginning: how to achieve reliable continual learning and meta-learning of new features.

Reliable Continual Learning

First, reliable continual learning is the cornerstone of the entire OaK architecture. Whether learning the value function and policy of the main task, or learning hundreds or thousands of Options and Models for subtasks, all components must be able to continually learn new knowledge at run time without forgetting old knowledge. Sutton clearly points out that we still do not have reliable continual learning algorithms for nonlinear function approximators, i.e., deep neural networks. Catastrophic forgetting remains a major challenge in deep reinforcement learning. Although there are many research directions, there is still no widely accepted, scalable solution.

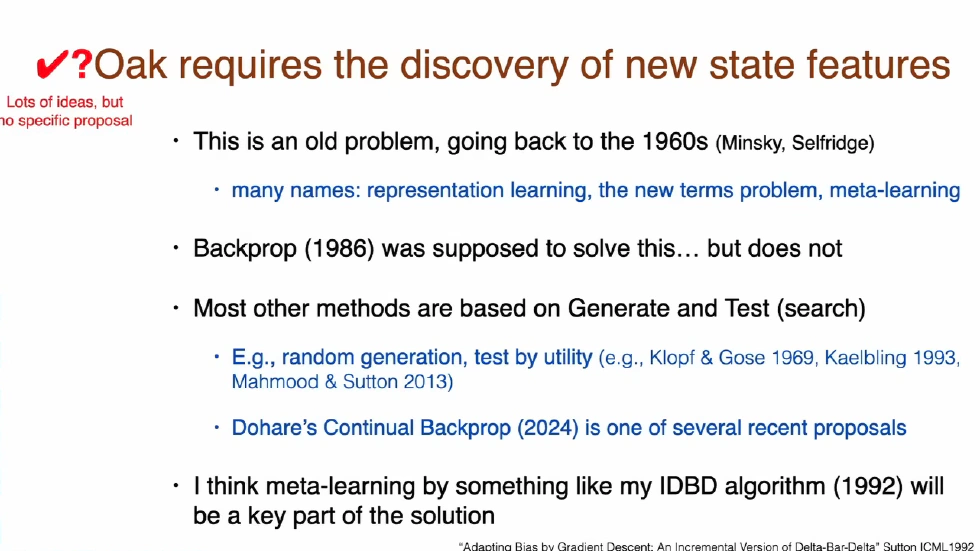

Meta-Learning of New Features

Second is meta-learning of new features, the starting point of the learning loop and the most challenging part. How can an agent, starting from zero, automatically and creatively generate useful new features? This is also known as the “new term problem,” which can be traced back to the thinking of AI pioneers like Minsky in the 1960s. Sutton believes that although the backpropagation algorithm proposed in 1986 was supposed to solve this problem, in practice, relying solely on gradient descent to learn representations is far from enough. Most current methods are based on generate-and-test ideas—randomly or heuristically generating a large number of candidate features, then evaluating and screening them by their contribution to downstream tasks. But how to design an efficient, scalable, and creative feature generator remains an open core problem.

Sutton believes that solving these two problems will be the most important breakthroughs in AI in the coming years. Once we have deep learning methods capable of continual learning, they will take over everything people currently do with deep learning.

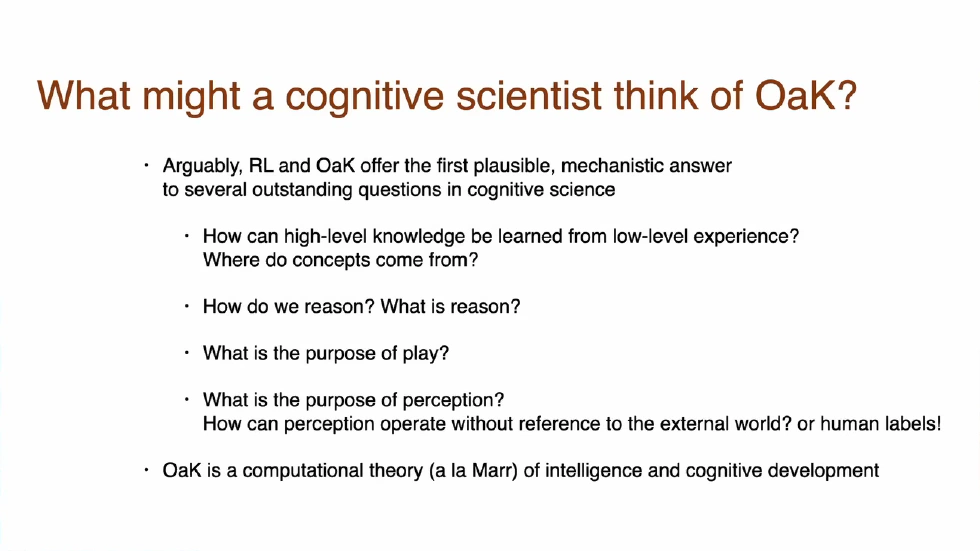

OaK as a Research Paradigm

It should be said that Rich Sutton’s OaK architecture is more of a manifesto or research paradigm than a specific algorithm. It reminds us not to forget the original dream of AI research in the race for model parameters and dataset sizes: to create an intelligence that can autonomously learn, understand, and transform the world.

Theoretical Answers Provided by OaK

Overall, OaK provides a highly persuasive computational theory of how the mind works, answering some long-standing questions in the field, such as:

- How is high-level knowledge learned from low-level experience?

Answer: Through cycles. - Where do concepts come from?

Answer: From features constructed to solve subtasks. - What is the essence of reasoning?

Answer: Perhaps it is planning based on Option models. - What is the purpose of play and curiosity?

Answer: To discover and set those subtasks that build our cognitive structure. - What is the purpose of perception?

Answer: To form useful internal concepts that can serve as the basis for subtasks, without the need for human-labeled supervision.

A New Framework for the AI Industry

For the entire AI industry, OaK also provides a new thinking framework and a grand vision to guide research for decades to come. It emphasizes several key capabilities that may be overlooked in the current large language model craze, including planning based on learned models, perception rooted in experience rather than human labels, and autonomous discovery of subproblems, options, and features.

OaK prompts us to rethink: what is true learning? And what is true intelligence? As Sutton said at the end of his talk, the vision of OaK is precisely how to cultivate an open-ended superintelligence based on run-time experience. If this path is correct, then AGI may begin with experience, grow through cycles, and reach infinity.

Conclusion

OaK provides a set of highly convincing computational theories about how the mind works, answering some of the field’s long-standing questions. It offers a new framework for thinking and a grand vision that can guide research for decades to come. It emphasizes several key capabilities that may be overlooked in the current large language model craze, including planning based on learned models, perception rooted in experience rather than human labels, and autonomous discovery of subproblems, options, and features. OaK makes us rethink: what is true learning, and what is true intelligence? As Sutton said at the end of his talk, the vision of OaK is precisely how to cultivate an open-ended superintelligence based on run-time experience. If this path is correct, then AGI may begin with experience, grow through cycles, and reach infinity.