Demis Hassabis Interview: Genie 3 Takes a Step Closer to AGI

On August 12, Google’s development lead Logan Kilpatrick had a conversation with DeepMind’s CEO Demis Hassabis. The interview was packed with information, covering not only the advancements in AGI but also the capabilities AI will need in the future, with a particular focus on DeepMind’s recently released Genie 3.

On August 12, Google’s development lead Logan Kilpatrick had a conversation with DeepMind’s CEO Demis Hassabis. The interview was packed with information, covering not only the advancements in AGI but also the capabilities AI will need in the future, with a particular focus on DeepMind’s recently released Genie 3.

What is Genie 3?

Genie 3 is a 100% controllable, real-time AI world engine. Many people have likely seen its video demo; some may think it is merely a high-end video generator. However, Genie 3 represents a concept that deserves serious discussion: the world model. Today, we will explore an often-overlooked question based on this interview: If an AI does not understand the world, can it still be considered intelligent?

Understanding the Genie Series Models

Before addressing this question, it’s essential to understand the Genie series models. Back in 2024, DeepMind released the first generation of the Genie model, which aimed to train AI to understand the world through video. At that time, it had very limited capabilities, capable only of generating short video clips based on user-input images or semantics. The quality was rough, with low frame rates and blurry images, often resulting in distorted character movements. It was much like our earliest experiences with Midjourney for images and Runway for videos.

However, DeepMind had grand ambitions hidden beneath the surface. They intended to use these videos as teaching tools, allowing AI to learn about physical laws, spatial dynamics, and causal relationships, much like a child learns fundamental concepts by watching cartoons.

Advancements from Genie 1 to Genie 3

By the time of Genie 2, it could generate more coherent 3D environments, such as a person walking or skiing inside a house. Still, interaction was limited. Most of the time, you could only watch AI perform short segments, without any ability to intervene or issue commands. Essentially, it was just an autoplay window. Moreover, Genie 2’s memory was fragmented. If you just saw a red snowboard, it might suddenly turn green in the next frame, or an object might disappear after being present for only two seconds. Thus, in practical terms, Genie 1 and Genie 2 were more like proofs of concept, demonstrating that we could use video to teach AI to dream of a world, but they could not maintain the continuity of that dream.

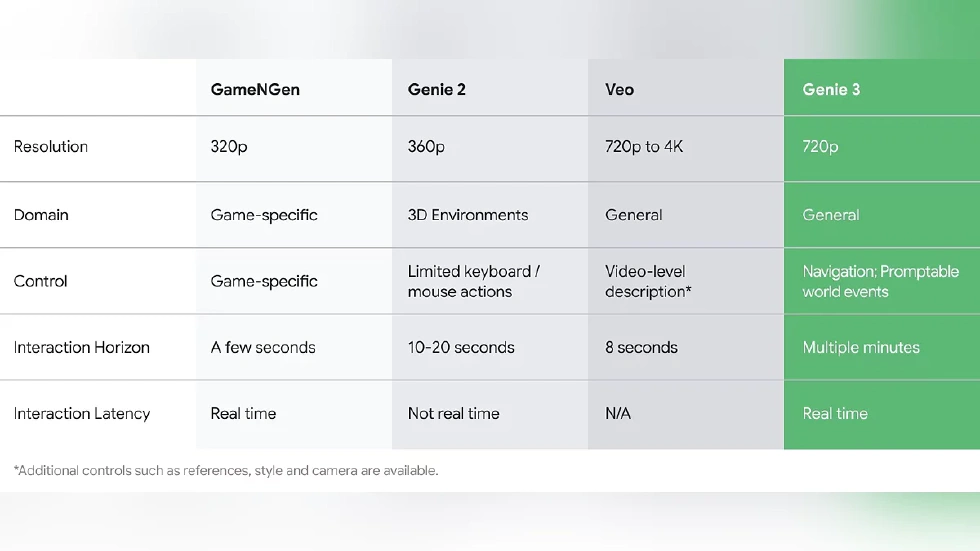

With Genie 3, everything changed. It not only improved the clarity of images to 720p but also generated visuals in real time at a stable 24FPS. This means when you take a step in the AI-generated world, it can instantly refresh the scene before your eyes without any lag, akin to playing an open-world game. The key here is that everything is created in real-time by the AI.

New Features of Genie 3

Furthermore, Genie 3 introduces the mechanism of “Promptable World Events” for the first time. You can not only walk and see but also give the AI real-time narrative commands. In terms of control, Genie 3 is no longer just a video viewer; it genuinely supports first-person navigation and real-time interaction, allowing you to experience life in a virtual world. For instance, if you want to transform a forest path into the AI’s world, you only need to provide a prompt like “running by a glacial lake, traversing branching paths in the forest, crossing flowing streams nestled between beautiful snow-capped mountains and pine trees, with abundant wildlife enriching the journey.” Genie 3 will immediately generate such an environment, allowing you to enter it and see how the water flows around the stones, how birds fly, and how sunlight filters down.

For example, if we wish to generate a hurricane scene, Genie 3 creates an interactive 3D environment where you can be surrounded by waves crashing on the road and palm trees swaying in the wind. Everything feels incredibly realistic, and all details are consistent in logic and physics. This explains why Hassabis emphasizes that Genie is the most critical step we’ve taken in understanding simulated worlds and one of DeepMind’s core dreams since AlphaGo.

The Challenge of World Models

In other words, the ability to generate a world is the best test of whether AI understands the world. You might wonder why, unlike GPT and other large language models that boast rapid advancements and a growing number of products, world models have never truly entered the public consciousness, with only a few companies making progress in solitude.

To comprehend this, let’s first ask ourselves: is training an AI to speak easier than making it understand the world? The remarkable progress in large language models in recent years is largely due to their inherent advantages: abundant data and low costs. There are TBs of text data available on the internet to crawl, including articles, novels, Wikipedia, and Reddit. Humanity has described the world in dense layers of language.

The core point is that language fundamentally functions as a one-dimensional sequence—one sentence follows another—making training straightforward. All it takes is predicting the next word, providing a low-cost, high-efficiency solution. However, for world models, the challenge is to predict the next world. The initial hurdle is data; models must be trained on video, physics, and causal data, which are not readily available. Simply relying on text is futile for training AI to understand the world; it requires images, videos, motion trajectories, physical dynamics, spatial structures, causal chains, and much more—information that is not just voluminous but also complex.

Data and Algorithmic Challenges

For instance, a single high-definition frame from a video is equivalent to tens of thousands of tokens, and a video can translate into millions of tokens. Furthermore, it involves temporal and spatial consistency and even interactions and feedback between characters. Thus, the world must be generated frame by frame. The crucial question is, where does this data come from? Unlike large language models that can scrape the web, it often has to create its own data.

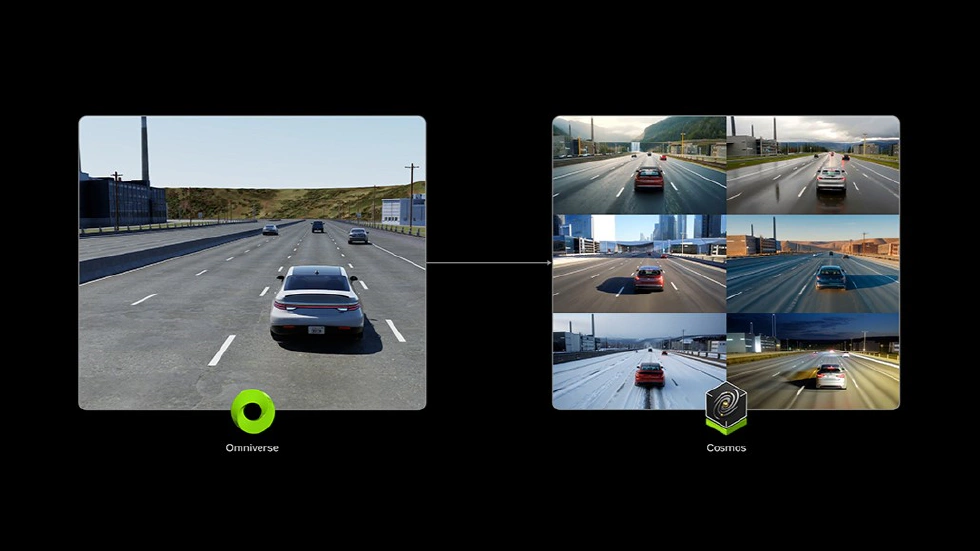

For example, DeepMind chooses to use the game Minecraft to synthesize environments, while Meta employs robots to gather first-person videos, and Nvidia’s Cosmos model relies on millions of hours of vehicle video, LiDAR data, depth maps, edge maps, and multimodal labels. Even if we can obtain the data, it must undergo a series of processes such as segmentation, denoising, annotation, deduplication, tokenization, spatial structuring, and cross-modal alignment. Nvidia once mentioned that training a model capable of generating just five seconds of 720p video requires PBs of video data and millions of dollars in GPU resources, a threshold that is nearly impossible for startups to meet.

Moreover, world models face algorithmic challenges. The task for large language models is to generate what are deemed reasonable sentences. Even if they are nonsensical, as long as they read smoothly, it may be challenging to identify issues. However, the world model cannot afford to be so; it must ensure causal validity, physical reasonableness, and spatial continuity. For example, if a cup falls off a table, it cannot suddenly disappear a second later; when a car turns a corner, it must maintain the same direction and cannot suddenly ascend to the sky.

Furthermore, if a character states they are going outside, they cannot immediately appear on top of a mountain. In other words, world models must not only generate content but also maintain the logical closure of that world. To achieve this, the model must construct a complete “world simulator” that can predict results, imagine the future, evaluate paths, and reasonably respond to unknown scenarios. The computational complexity behind this is exponentially greater than that of large language models.

The Future of World Models

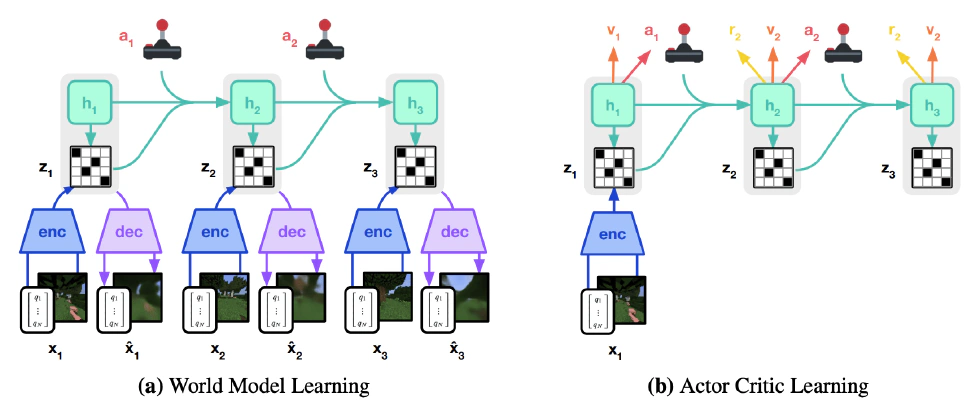

For instance, in the case of the Dreamer V3 algorithm, to allow AI to simulate the Minecraft environment, it must predict images, rewards, termination signals, and behavioral feedback in every frame. Each item is interconnected, and a single mistake can lead to complete failure. Additionally, advancements in large language models have largely benefited from the Transformer architecture and the increase in computational power, with larger context windows and larger parameter scales. However, world models cannot solely rely on brute computational strength to solve problems because they are facing far more complex issues; they need to perceive images while predicting movement, remember the past, and simulate the future, generate details, maintain logical coherence, and consider the causal chains from actions to feedback to outcomes.

Thus, different companies are experimenting with their hybrid architectures. For example, DeepMind’s DreamerV3 uses a recurrent state space model (RSSM), Nvidia’s Cosmos-Reason1 employs a combination of Mamba, MLP, and Transformer, and Meta’s NWM utilizes a conditional diffusion network (CDiT) aimed at reducing FLOPs. If the success of GPT stemmed from compressing all human language into a predictor, then the success of the world model relies on creating a self-consistent microcosm from visuals, actions, causation, and other elements. If the former can be seen as copying a book, the latter is akin to crafting an entirely new novel.

It should be clear which endeavor is more challenging. So, given the difficulties of creating a world model, why pursue it? Because it is one of the closest paths towards AGI. It could be said that without a world model, it would be impossible to achieve true artificial general intelligence. The foundations of human cognition have never been language; rather, they are based on experience. Language is merely our way of recording the world, not a way to perceive it.

The Importance of World Models in AGI

German computer scientist Jürgen Schmidhuber pointed out long ago that if an embodied intelligent agent wants to learn effectively, it must construct an “internal model” of the environment in its mind—the so-called world model. With this, the agent can create a loop of “action, feedback, update” in imagination without real interaction costs, allowing it to learn from dreams, iterate through trial and error, and derive universal strategies. This notion was systematically validated in the 2018 paper “World Models,” in which researchers trained a generative RNN network to simulate game environments and subsequently trained control strategies in these simulated worlds. The strategies practiced solely “in dreams” could directly execute tasks in real gaming environments.

Turing Award winner and Meta’s chief scientist Yann LeCun also places world models at the core of AI research. He publicly emphasized that without modeling the world, AI cannot engage in true reasoning. His proposed JEPA (Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture) model attempts to transcend pixel-level modeling by predicting abstract representations of hidden states, emphasizing a model’s ability to predict future latent representations rather than generating pixel by pixel. This approach closely resembles human cognition, as we do not reconstruct images frame by frame but rather infer how the world will evolve based on abstract models.

If large language models are the “logical hub” of the brain, then world models equate to the “motor cortex” and “sensory neurons” of AI. Without these components, AGI will remain confined to verbal articulation. Additionally, world models are not merely about creating a simulator that “looks like the world”; they provide agents with the space to explore behaviors and trial-and-error, serving as the projection space for the agent’s consciousness, the foundation for planning and rehearsing, and a critical precondition for enabling agents to make autonomous strategic choices without human prompts.

Conclusion

So, returning to that initial question: If an AI does not understand the world, can it be considered intelligent? Genie 3 provides the answer: no, at least not in the truest sense of intelligence.

Of course, we can enable large language models to imitate the appearance of a “smart person,” allowing them to score well on tests, reason, or write coherent articles. However, their “intelligence” resembles that of a child who has never left home, understanding the world only through others’ descriptions. When you say, “an earthquake is coming,” it imagines words instead of the ground shaking. When you state, “the wind rustles the leaves,” it visualizes a series of words rather than hearing the rustling sound.

Reflecting on humanity, we are not deemed intelligent merely because we can speak; rather, it is through falling, stumbling, feeling the wind, and getting drenched in the rain that we gradually comprehend our world, leading to subsequent thought and expression. Thus, true intelligence must begin with the perception of this world. As we look further into the future, Hassabis suggests in the interview that models like Genie, Veo, and Gemini—currently relatively independent—are destined to gradually merge, forming what we call an “Omni Model.” This model will be capable of processing language, multimedia, and performing physical reasoning and content generation, representing the ultimate path towards AGI.